For 85 years The Turk, a clockwork wooden chess

player, toured Europe playing chess -- and winning. Pure

technology -- or magic?

The Agony Column for May 21, 2002

Commentary (a day late and a dollar short) by Rick Kleffel

For 85 years The Turk, a clockwork wooden chess

player, toured Europe playing chess -- and winning. Pure

technology -- or magic?

It's been almost a year since I worked for the company that had, at one time, used Clarke's famous quote in their advertising copy. I worked there for ten years, so I have a pretty strong claim for being familiar with the process of putting magic in a box. It's not easy. It takes authentic genius somewhere back at the beginning. After that add a mountain of good engineering. And you've still just got a box. Until you show it off.

Only the user can put the magic in a box.

Only the viewer, the one with the eyes, the one who does not know the limitations of the box can turn a bit of genius, engineering and showmanship into an open-ended solution to vaguely stated problems. If I just had that box, the user tells themselves (or anyone who will listen), I would hold magic. I could create something from nothing.

Boxes have concealed magic since Pandora opened hers back in the mists of time. I'll admit I've lusted after my share of techno-fix magic boxes. In my case they were electronic musical instruments that would create the music I could almost hear in my mind. Alas, as I no longer work for the magic box makers, I have to contain my desire, rope it in and work with what I've got.

But the best boxes may not be those that can actually do what they appear to. The best boxes are the ones we don't have, the ones we can't quite get, the ones on stage. At that point, the dreaming is unencumbered by the actuality of having to use the box. Until you pick up the guitar, you can easily believe that you're Eric Clapton.

|

|

Tom Standage's non-fiction work 'The Turk' is a gripping and entertaining story of science, art and illusion. |

An excellent example of perhaps the ultimate magic box is to be found in 'The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine' by Tom Standage. He's unearthed the story of a stage machine that inspired some of the geniuses of the Eighteenth Century to invent the world as we now know it. It's a fascinating, page-turning piece of non-fiction that operates in a landscape more baroquely grotesque than has been imagined by any of our steampunk favorites.

|

|

Madison Priest invented a revolutionary method for transmitting data over twisted pair phone lines. No, it's NOT DSL. |

Of course, the magic box is more common in the 20th century. Beyond the electronic keyboard of the month, or computer gadget of the month, there are boxes that promise a revolution, boxes that bring big money like a shoal of sardines brings the salmon. In 1995, one Madison Priest first began demonstrating a box that could break down barriers in the burgeoning world of the Internet, and make billionaires of those who owned the technology. It gave computers the ability to communicate at speeds 1,000 times faster than a conventional modem over a simple telephone wire. It inspired first and foremost an investor's feeding frenzy. Video on demand could fundamentally alter the landscape of the video business. Madison Priest had the box that would make the dreams come true.

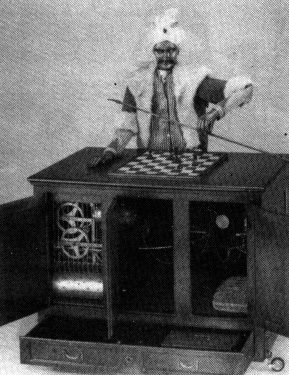

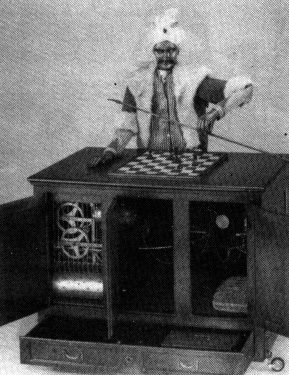

To many, Priest's invention sounds improbable. But then so did 'The Turk'. Standage's work of non-fiction really does read like a biopic of the chess-playing machine. He begins with its ancestors, the 'automata' of the eighteenth century, mechanized ducks and flute-playing statues that operated on clockwork and bellows-pumped air. The Turk was born in 1769, fathered by Wolfgang Von Kempelen, a Hungarian nobleman in Empress Maria Therese's court. It consisted of the life-size figure of a man carved from wood seated behind a cabinet on top of which was a chessboard. The cabinet could be opened to show the clockwork inside. The machinery was displayed to show that it was indeed only a machine, then the Turk would proceed to play chess, picking up pieces and moving them in response to his opponent. It played well, and only rarely lost. It was the first time that humanity was faced with a man-like machine that could outperform a man.

|

|

This engraving of the Turk is reproduced in Standage's outstanding book. I keep wanting to call it a novel, because it's focused and reads like lightning. |

Surprisingly, The Turk did not inspire fear. It inspired invention. It suggested that there was no limit to what man could achieve. Whether or not it actually played chess using clockwork -- and there were some reasons for the audiences of that time to believe that it could -- by its existence, it put forth the proposition that such a thing could exist. Of course there were those who tried to explain it, but it was too clever for most of them. Standage eventually explains the Turk, but not until we've seen it tour Europe, and inspire a wave of invention from the telephone to the detective story to the first computer. The Turk's tours are exciting, lavish recreations of the late Eighteenth and early Nineteenth century world of show business.

|

|

Playbill for the return of the Turk. After the death of the inventor, it was sold Johann Nepomuk Maelzel, who maintained the mystery for many more years. |

Of course, show business hasn't changed much in the intervening years. And the import of technology developed to help showbiz hasn't changed much either. Witness this comment by David Brewster in the 1830's: "...those automatic toys which once amused the vulgar, are now employed in extending the power and promoting the civilization of our species." There's a lot of money to be made in show business and it can support some pretty wild research. We have only to look to the megaplex movie theaters to see technology developed for show business that has far-reaching implications. When the movie 'Forest Gump' came out in 1994, it showcased state-of-the-art technology to put words in people's mouths. Now, that same technology has hit the next level and it's a cause for some concern. Even the inventors have some reservations.

'The Turk' explores that strange nexus of technology and illusion, of science and art while telling the exciting story of a travelling show. It's a story that is still being repeated to this very day. It's the most basic question of any creation, and it's been best summarized by an advertising sloganeer -- 'Is it real or is it Memorex?'

This question delves into the heart of any presentation. Especially when there's lots of money involved. Earlier this month, in the online edition of the Florida Times Union, reporter Matthew I. Pinzur tells the story of another magic box.

|

|

Madison Priest, inventor of the magic box that would (will?) change the Internet as we know it. He was a master showman and a major control freak. |

In 1994, one Madison Priest, then a resident of Palatka, Florida, demonstrated a bit of technology that has the potential to change the world. He was a forty-something high-school dropout who had worked for Martin Marietta. Using technology he claimed to be derived from low-energy or zero point physics, he had invented a device which could send data over ordinary phone lines at 1,000 times the current standard. He could play video on one computer and transmit it seamlessly to another 1/2 a mile across a river over the phone. "He had a Holy Grail that was the telecommunications equivalent of cold fusion," an investment banker commented.

Priest's demonstrations electrified these men. He enabled them to see themselves as brilliant early-adopters, promised them a stake in something that clearly had the potential to exceed the market grip of Microsoft. "I thought I would be the guy who finally got this technology developed," one of his early investors said. "That was my supreme arrogance...If you didn't jump on this, some big company would get on it and you'd be aced out." But big companies loved the show as much as anyone did. Blockbuster poured something in the range of $2 million; Teddy Turner, son of CNN mogul Ted Turner helped to create Zekko Technologies in 1997.

|

|

"I want to Believe." Linda Priest at one of her husband's demonstrations. Eventually they would confess that they had help from aliens they called 'hoppers'. |

By 1998 the American Psychological Association Telehealth Conference was touting his technology. "A special hands-on equipment presentation will be offered by Tie Communications and Zekko Corporation...Come Experience this equipment and get your own sense of it for psychotherapy!" enthuses the web page. Investors were treated to demonstrations of a technology capable of every Internet junkie's wet dreams. According to Pinzur, "investors saw that same computer send video instantly. The Eagles performance of Tequila Sunrise showed up on the second computer in digitally perfect full-screen glory, the music as clear as a compact disc...Even with top-grade fiber optics, that kind of quality was rare at the time..."

Priest was a real showman and a control freak who carefully staged his shows for maximum effect. It helped to counteract his image with investors who "were put off by his rural Florida twang, his T-shirts that said "rocket scientist" and breath so bad it could choke a man in close conversation." But the attachment of Turner, the implication of CNN involvement, Blockbuster's millions, all of it gave Priest an air of authority. One investor lead to another, then another. The Priests were taking in millions, most of it going directly to them. There was only one hitch in the whole affair, one last stop before world conquest. Priest had to move beyond the show, to let the box off the stage. He had to turn over prototypes.

|

|

Is this forty-something ex-con from Florida another Einstein? Folks connected with CNN, Intel and Blockbuster bet millions that he was, in spite of his dental hygeine problems. |

Records show Priest claimed at least ten working prototypes were fried by lightning strikes. Others were destroyed by fire and floods. Still, investors held out hope. A Texas physicist who dealt in low-energy physics confirmed that "His ideas are interesting and provocative, so he's got a good story." After a car crash incapacitated him, Priest's investors were frantic to have him document his work. But Priest said that he did not feel safe putting his secrets in a form where they could be stolen. After all he had the spec for the Holy Grail. He wasn't about to see it published on the Internet.

As his failures to appear piled up Priest lost investors, but gained new ones. "The bigger the fish you go after, the less likely they are to come after you...They don't want to admit being taken by a flimflam man from Palatka." As Blockbuster fell away, prestigious Line One Technologies looked to invest in Zekko. Intel recently acquired line 1 for $2.1 billion in stock. But before they were, they went after Turner in court for his involvement in Zekko. He claimed to have seen nothing, heard nothing, known nothing, and evidence suggests that might be the case. He resigned from Zekko in 1998, leaving his money behind him.

Even as Priest's failures to provide the prototypes piled up, his ability to bring in new investors continued. "If he thought his audience was really clueless, he would really spread it on," said an investor and later a partner. By September 1998, Zekko had $6 million, with another $36 million in waiting. But after a critical show in Chicago, investors finally got a look inside the magic box. It was not a pleasant sight.

Priest's computer -- the computer he performed his demonstrations on -- was not a computer at all. Inside the metal box was a VCR. Investors went scrounging through Priest's riverside warehouse, where he performed his famous transmission via phone lines across the river. In the warehouse, they found that the power strips used to plug in his computers contained coax cables with the power cable. And outside the warehouse they found 1/2 mile of coax cable looping into the river itself. Alas, there was no magic in the box, just a bit of technology. The magic had always been in the spectator's brains.

|

|

Priest's invention which was never proved in protoype to work over phone lines, now works in the wireless world. That is, in the magic world of our tiny brains. |

But wait -- there's more! As Priest was being sued for misrepresenting his twisted pair invention, he claimed to have perfected a wireless version. Investors were still interested, even though he had at one point told Turner that an alien being called a hopper had brought his invention to him. For every show he performed, he had a cover story as to why his detractors were wrong. He would invalidate his own excuses, circle and loop back on himself, then up the ante and move on to international investors. His wife ratted him out, then claimed it was all down to the stress of having an innovation so brilliant it could alter the whole landscape of the Internet. The Priests live in a huge house, and have new claims of spectacular Invention. His words set the minds of his investors on fire.

Pinzur's account of Priest reads like the 21st century version of 'The Turk'. Both of them read like science fiction -- aliens, robots, and magic technology. Yes, we now have the chess-playing computer Deep Blue, just as we will eventually have a working version of Priest's "ansible". Deep Blue did change the world, though arguably not as much as the Turk. Had Priest's invention worked, the bubble might not have burst, and the Internet could have grown unchecked, reaching new levels of Multi Level Marketing. By the time it is invented -- even if it is by Priest, in a wireless version -- the presentation will have deflated the idea of some of its import. But there will always be new magic boxes with new promises. And there will always be new showmen and new audiences waiting, rapturous. Waiting for someone to set their minds on fire.

Thanks,

Rick Kleffel

Acknowledgements: Material in this essay was developed from news aritcles by Matthew J. Pinzur of the Florida Times Union. Quotes from his news articles are, uh quoted, and links to the articles are in the essay.