|

|

Space opera was born with EE Doc Smith's Lensmen series. So were many science fiction fans. |

|

|

|

The Spectrum of Space Opera

The Agony Column for October 3, 2002

Commentary by Rick Kleffel

Finishing 'Light', I realized the obvious. There are an infinite number of universes in which to set space operas, and an infinite number of styles in which to write them. But in that infinity squared there's a pretty clear spectrum of style that makes it to the book racks. From the light-duty feel of prequels for familiar favorites to the densest knot of linguistic bravado, there's a definite gradation that allows readers to find the perfect mix of any of the aspects of space opera that appeal. In the past couple of weeks I've stumbled across two ends of the range and found myself enjoying both. What's interesting to me is that space opera in the end is no different than any other genre or even novels that lack genre. Behind the assembled elements of the prose and the plot, the temperament of the writer reigns. Some space operas full of the elements -- interstellar space travel, galaxy-spanning cultures, aliens, space battles, political intrigue -- read like comfortable bestsellers. Some, using the same elements read like edgy modern character studies, others exotic experiments that push the boundaries of language. Yes it's obvious. Even in the strict confines of a rather rigid sub-genre, where, conversely, writers are free to roam the infinite universe, in the end the author's voice shines through.

|

|

Space opera was born with EE Doc Smith's Lensmen series. So were many science fiction fans. |

Space opera was some of the first science fiction I ever read. Back in seventh grade, at a time when the United States space program was sending men to the moon, I discovered E. E. Doc Smiths' Lensmen novels. They knocked me off my feet, which was a good deal easier back then. I thought these novels were so great that I convinced my seventh grade English teacher to read them. Like many, he enjoyed the first but found the scale-up and repeat format a bit tiring. It didn't dim my enthusiasm though. It rather boggled my mind recently when I realized that these had gone out of print. How could that happen? Fortunately, Michael Walsh of Old Earth Books felt the same way, and recently reprinted the series. They've been a huge hit for him, and helped underwrite his project to reprint the novels of Edward R. Whittemore, discussed in an earlier column. At WorldCon last month, he told me that the galleys for that project are close to hand. Space opera saves the day again. And somewhere out there, a seventh grader is discovering the Lensmen.

|

|

Don't bite the hand that feeds readers all this great science fiction. Media tie-ins are pulling your basket out of the fire every single day. |

These are good times for space opera. Media tie-in space operas are in a sense supporting the whole science fiction genre. Standalone written space opera is once again prominent. It's a vibrant, healthy little corner of science fiction with a wide variety. Recently, I've read works that range from page-turning retro SF bestsellers to dense linguistic experiments. I'll admit to enjoying each on its own terms. Now, I know that there's a lot of material I've missed. That's because one could make a career of reading only space opera. But the works I've read do have such a wide range, the reader can see the spectrum of nearly all fiction within the microcosm of this one little sub-genre. I'm going to take the reader on a journey from the lightest and easiest-reading to the darkest, densest realms of literary experiment.

|

Author(s) |

Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson |

Neal Asher |

Frank Herbert |

Peter F. Hamilton |

Alastair Reynolds |

M. John Harrison |

John Clute |

|

Name |

The Dune-iverse |

The Runcible Universe |

The Dune-iverse |

Night's Dawn / Confederation |

Conjoiners & Demarchists |

Kefahuchi Tracts |

Okey-Dokey Verse |

|

Novels |

Dune: The Butlerian Jihad, Dune: House Atreides, Dune: House Harkonnen, Dune: House Corrino |

Gridlinked, The Skinner, The Line of Polity |

Dune, Dune Messiah, God-Emperor of Dune, Chapterhouse Dun, Heretics of Dune |

The Reality Dysfunction, The Neutronium Alchemist, The Naked God, A Second Chance at Eden, The Confederation Handbook |

Revelation Space, Chasm City, Redemption Ark, Diamond Dogs, Turquoise Days |

Light |

Appleseed, Earth Bound |

|

Difficulty Level |

Bestseller-style page-turners. |

Classic SF that's more complicated than it seems. |

Venerable SF series suggests stuff way beyond the text; comes with a glossary and several appendices. |

An entire 202 page handbook explains anything you can't get from the 3,000 pages of fiction. |

Dense and textured, it's compelling enough to keep you around for the revelations. |

Easier to take than any psychedelic prescription with comparable effects. |

Fiction by the gentleman who wrote the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. |

|

Rewards |

Lots of fun seeing the beginnings of one of the SF classics. |

In-your-face-action and horror give way to layered complexity. |

Deep understanding of planets that probably don't exist. |

Two month vacation in the universe at large and your easy chair. |

Visions of the current world rotting about your feet. |

Better than any psychedelic prescription that your doctor won't give you. |

You're a genius. |

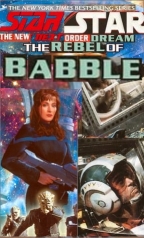

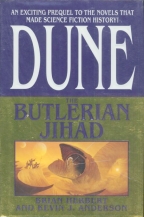

I'll start out with a recent and oddly light entry into the world of space opera, the retro-SF bestseller 'Dune: The Butlerian Jihad', by Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson. While the original 'Dune' novels would fit more in the middle of the range, and have recently been re-issued in sturdy, nicely produced hardcovers by Ace, these prequels are a bit different. They've received a mixed reaction on the open market. On one hand, they're enormous bestsellers, sometimes hitting the standard fiction bestseller lists. On the other hand, they've generated the kind of vituperative criticism on Usenet that gives newsgroups a bad name. I'll admit that I might not have read this novel had I not been asked to by KUSP. But having been handed the book, I found myself pretty damn well captivated. Herbert and Anderson have a decidedly retro take on just about all the SF tropes. It's as if they ignored 20 years of SF literary history, particularly in their concept of AI. I found myself thankful for that. I first read 'Dune' when I was 12. If I was 12 today, 'Dune: The Butlerian Jihad' could very well be the novel that would hook me on science fiction. It might also hook me if I was 52, had never read a science fiction novel in my life, and my only experience of science fiction came from 'Star *'.

|

|

|

The father of great science fiction is re-issued by Ace. |

Brian Herbert, the son of Frank Herbert, and Kevin J. Anderson offer enjoyable glimpses into the future's past. |

'Dune: The Butlerian Jihad' delivers on a number of levels. It offers some interesting thoughts on slavery -- of the whips and chains variety. It offers glimpses into the beginnings of technologies and cultures that readers of the original series will certainly recognize. It successfully made me go goo-goo-gaa-gaa at every single one of them. It was certainly exciting enough, with space battles that Doc Smith himself would slaver over. And it had a healthy dose of space opera's namesake -- that is, soap opera. Not overbearing mind you, but enough to make the reader realize that all the galaxies and all the aliens and all the technological extrapolations won't matter one whit if the reader doesn't care about the characters. I'll be back for further Dune prequels. To this reader, they're a breath of fresh air.

|

|

|

Asher's space opera starts out with an interplanetary James Bond tale that's every bit as enthralling as the best Sean Connery has to offer. |

This novel starts out on a grim note and grows surprising resonant. |

If you'd care to step to the right a bit, I'd like you to take a look at the novels of Neal Asher. Asher's novels of the Runcible Universe, 'Gridlinked' and 'The Skinner' offer a slightly skewed version of space opera. Asher has all the checkpoints -- interstellar travel, lots of planets that are very alien, some alien aliens as well, human intrigue and political machinations. But Asher also offers the reader a pleasantly grim nod-and-a-wink as his universe literally chews up, swallows and spits out his characters. Whether they're emerging from unreliable runcible portals or the maw of a huge oceanic monster, Asher's characters and situations have a light, deft touch that belies his heavy-metal settings. Asher's novels only seem simplistic at first. He slyly layers his characters and settings, building up a complex picture before the reader is aware of what's being done. There's some clever writing that goes on here -- clever and one hell of a lot of fun. I've covered Asher extensively in earlier columns, and even an interview. Be careful when reading that interview. If you read his fiction, you'll be aware that he does have a bit of bite.

|

|

|

Readers who bought this novel when it first came out turned out to be quite lucky. |

Yes, 'Fallen Dragon' is in fact smaller than 'The Reality Dysfunction'. |

The novels that probably got me reading space opera in any serious way recently were those of Peter F. Hamilton. His 'Night's Dawn' Trilogy came out of not left field, but the grocery store. At least, that's where I first saw them. I wrote them off as sub 'Star*' trash, to be honest. Didn't want anything to do with them, though the mention of Stephen King elements on the cover seemed a bit intriguing. So when a friend loaned the first half of the first novel to me (in the US, each of the three novels was split, turning the trilogy into six books), I read the first few pages and was immediately hooked. I'd read Hamilton ages ago in the gone but not forgotten 'Fear' magazine, one the UK responses to the 80's horror boom that so fractured the horror genre. As an utterly compulsive book buyer, I immediately went online and found a UK hardcover of the first novel, 'The Reality Dysfunction'. Not only was it a great book, it proved to be a great investment -- it's now worth about 20 times what I paid for it.

The 'Night's Dawn' trilogy and the two associated books -- 'A Second Chance at Eden' and 'The Confederation Handbook' -- probably add up to a bit too much writing. That said, I'd complain furiously if any editor shaved them down. This is space opera at its most immersive, a literary overkill that takes no prisoners. It's also filled with excellent and innovative versions of all the space opera staples. Dueling cultures, huge concepts, alien artifacts and larger-than-life heroes roam the universe created by Hamilton. But the cover blurbers aren't kidding about that Stephen King element, either in the gore or supernatural.

With three novels that use up more than 3,000 pages, the 'Night's Dawn' trilogy might be a bit overwhelming for readers who want to experience Peter F. Hamilton's excellent writing. For them, there's 'Fallen Dragon', which takes place in an entirely different universe, but offers many of the same pleasures in a single volume. Now, to a certain extent, space opera is usually thought of as series fiction. I'm allowing single volume works into my definition, and 'Fallen Dragon' is an excellent example. It has all the pleasures of the space opera -- characters with tangled emotional lives, galaxy-spanning cultures, alien artifacts, but only 600 or so pages. If you like space opera and haven't experienced Peter F. Hamilton, here's a good way to do so. Then prepare to lose a month or more of your life reading the 'Night's Dawn' novels.

|

|

|

'Revelation Space' lived up to its title. The tight geo-synchronous orbit makes it appear larger than 'Redemption Ark'. |

'Redemption Ark' is the second novel in a series to be completed with Reynolds next work. |

The next step in the sliding scale is the work of Alastair Reynolds. His novels -- 'Revelation Space', 'Chasm City' and 'Redemption Ark' -- certainly qualify as one of the best space operas any reader could ask for. I've covered these books extensively in other columns. To me, they're some of the best science fiction being written today. Given what I heard at WorldCon, most of the SF world seems to agree. They're dark, dense, filled with innovation and complex characters. The characters are more twisted and their troubles deeper, less savory than those of the previously mentioned works. Reynolds does some innovative riffs on the staples of space battles that effortlessly re-invent the whole idea. If Stephen King hangs over 'Night's Dawn', then Clive Barker hangs over Reynolds' work. There's an edgy nervousness at work here. It gives the novels an electric energy. (An interview with Alastair Reynolds is available here.)

|

|

|

Ken Macleod's socialist future of 'Cosmonaut Keep' is an idiosyncratic space opera. |

'Dark Light' goes further into the universe created in 'Cosmonaut Keep'. |

As we step further to the right, it's inversely appropriate that we should encounter Scottish socialist Ken Macleod. His first four novels, the Fall Revolution sequence, skirted the edges of space opera. But his most recent two novels, 'Cosmonaut Keep' and 'Dark Light' have every checkpoint of standard space opera. Of course, a purely socialist state would have every checkpoint of statehood but still be almost unimaginably different from the capitalist equivalent. This is no less true of Macleod's novels. 'Cosmonaut Keep' starts out in a very near future of struggling computer systems administrators but ends up in the far-flung cosmos with faster than light travel and human colonies extracted from the world at various points in past history. Macleod's universe is a herky-jerky jump-cut assemblage of all types of fiction, but he stops for the soap opera aspect of space opera as well as the aliens. The political intrigue is so dense as to be practically impermeable. For some readers, this is the charm of space opera via Macelod. There's clearly more going on in this universe than is seen. Other readers might find it a bit dislocating. But there's no denying the pure sense of purpose and integrity in Macleod's fiction. Space opera with a heavy socialist twist is clearly something this world needs.

|

|

M. John Harrison offers up the text equivalent of '2001' for the year 2002. |

M. John Harrison returns to the world of space opera in 'Light', the newest and latest novel discussed in this article. Harrison has had a long career of breaking rules, melding genres and writing about what readers least expect. From the magic realism SF of 'Signs of Life' to the tormented psyches exposed in 'The Course of the Heart', from the groundbreaking fantasy of the 'Virconium' novels (now available as one from Gollancz in the UK) to the groundbreaking SF of 'The Centauri Device', Harrison has managed to re-invent just about everything he touches. 'Light' is another fine example of Harrison's iconoclastic fiction. It is told in two story threads, as Michael Kearney and Brian Tate invent the quantum computer today that drives the far-flung starships of four hundred years from now. Harrison takes space opera and pulls it apart like a child pulling on taffy. He drives his current-day characters to extremes of invention that range well into psychosis. His surreal take on urban life feels as disturbing and dislocating as waking up hung over in city and finding out you don't know the language. His far-flung future is so changed as to be completely alien. The humans of the future in this novel are at first barely recognizable as such. But Harrison goes for broke and breaks the bank with his final thrust. He carefully illuminates the questions he's raised and answers each at the appropriate time. He creates mystery and even when he reveals what's behind the mystery, the luminous feeling of there being something just beyond the narrative remains. 'Light' is a challenging book that rewards reading and inspires re-reading. It's the reason you buy hardcover novels, because you know that you will turn those pages again.

|

|

John Clute re-invented not only science fiction but a goodly portion of the English language to bring readers 'Appleseed'. |

At the edge of the universe, there is only language. And at the edge of space opera, there is only John Clute. Having written the encyclopedia on SF, he's certainly the best set to write the 'Finnegans Wake' of SF. His first novel, 'Appleseed' certainly comes as close as one could hope to realizing that goal. Linguistically challenging and intellectually rewarding, Clute takes space opera and science fiction itself about as far it can go. 'Appleseed' almost seems like a document sent back from some future that we never imagined would come to pass. Yes, there are alien civilizations, and they coalesce just this side of comprehensibility. The humans have changed nearly beyond all recognition, and Clute's incredibly impressive language reflects this. If this were a hypertext novel, then nearly every word would end up being a link. A panel at the recent WorldCon suggested that hypertext fiction would not be a significant part of the future of science fiction. Reading novels like this (or those by Kim Newman, or Jasper Fforde), I would tend to disagree. Yes, the first time the reader tackles 'Appleseed', they should just read the text. It's an authentically mind-boggling experience. But were I to have a hypertext version, then I could really clue in on all the incredible history and research that went into this text. You know those pictures that turn out to be comprised of much smaller yet equally whole pictures? That's what 'Appleseed' is. It's more than a novel. It's the experience of a life that will never and can never be led.

When you've finished 'Appleseed', you'll really have completed a journey, not just through the science fiction genre, but through about any genre. They all have this spectrum, this range of excellent reading that can provide a huge variety. The limitless nature of science fiction is itself a fiction. Science fiction loves to limit itself, and then within those limits, find an infinite fractal expanse of possibility. The prospect is bracing. Within one little corner of one little genre, there's a wealth of good reading. Now, turn around slowly. There's the rest of the literary landscape. And you thought science fiction was limitless.

Thanks,

Rick Kleffel