| Agony Column Home | |

A Queer Eye on the Mean Streets

The Agony Column for

November 20, 2003

Updated with new Illustrations March 1, 2004

Commentary by Terry D'Auray

|

|

|

| Raymond Chandler defined the "mean streets". |

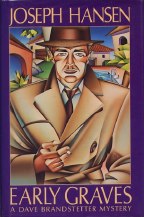

Joseph Hansen

wrote his first Dave Brandstetter novel 'Fadeout' in 1967. He wanted

to write "a good whodunit", but he also "wanted

to right some wrongs". He followed with eleven subsequent

wrong-righting Brandstetter books; the last 'A Country of Old

Men' published in

1991. While Brandstetter is not a card-carrying detective, we'll

give him

his bone fides. He's an insurance investigator in LA, ferreting

out scoundrels or scammers who are bilking his insurance company

for mega

bucks, which back then was a bad thing, or who are killing people,

which is still a bad thing. He's middle-aged at introduction,

none too swift-of-foot or fierce-of-fist, but he makes his way

quite

ably by being smart and shrewd. And he's also gay, matter-of-factly,

oh-by-the-way,

but openly gay. In 1967!

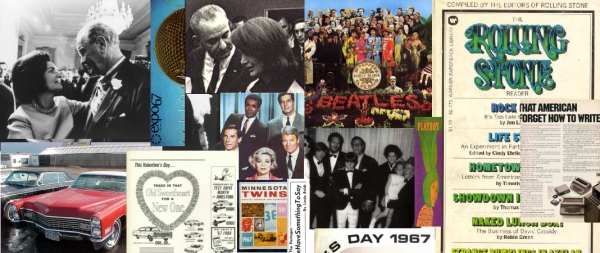

Think back. In 1967, Lyndon Johnson is President; the Chicago Democratic

convention and riots haven't happened yet; The Beatle's Sergeant Pepper

is the top album (no CDs yet); Jackie O is alive and not yet married

to Ari; 'Mission Impossible' is the number one-ranked TV drama (and

The Monkees won the Emmy for best TV comedy - yeah, yeah, yeah, I'm

a believer); Roe v Wade is 9 years off; and The Rolling Stone printed

its first, yes very first, issue. AIDS is undiscovered, and Stonewall

is just another bar in New York's West Village. Here's Hansen, writing

a novel about a middle-aged gay insurance investigator with nary a

wisecrack or serial killer, and getting it published! Well, getting

it published three years later in 1970, by Harper and Row. Viewed

from 2003, that's all pretty tame stuff. But in 1967, even 1970, it

was neither tame nor stuffy.

Hansen was a surprising low-key writer to be breaking such

new ground. (Not to imply that he's no longer around. He's

alive,

just not writing.)

He blended setting, plot and characters in stories that were

timely and perceptive, but sensible and realistic, suspenseful,

but above

all, quite calm. Unwilling to sensationalize his character,

and eschewing "action-packed" in

favor of modest violence and taut tension, he created Brandstetter

as a tenacious semi-plodder with brains not brawn, so unassuming as

to be wholly believable and wholly inoffensive. Just a regular gay-guy-next-door.

Nothing lurid, nothing risqué, nothing scary to the

70's reader. Nothing even particularly genre shattering, unless

you

believe, as

many did then, that a gay detective is, by definition, genre

shattering.

Hansen was completely up-front and unapologetic about his character's

sexuality. Brandstetter's serial relationships with men, from hunky

young things to older, wiser soul mates, are openly and unabashedly

described in each of his novels, with honesty and tenderness at times,

with exasperation and despair at others.

Hansen's books reflect the gay world, and many of his plots

involve gay characters, but he treats the entire gay theme

routinely. By so doing, he delivers the message that homosexuals

are quite

ordinary,

basically no different from anyone else, a message none too

extraordinary

now, but at that time, not at all common. Homosexuals in mysteries,

if they appeared at all, were vilified scum. His books often

feature parallel stories, one a Chandleresque story of crime

and the other

a story of gay relationships and sexuality that turned the

clichés

of the time upside down. His writing is elegantly styled,

witty and descriptive, and his dialogue rings true. He is,

looking

back, a great

chronicler of the LA of the late 60's and 70's, describing

in readable detail its houses, cars, food and fashion, bars

and

nightlife. Of

course, those descriptions now would send the 'Queer Eye'

Fab Five to their cell phones, frantically dialing 911-Pottery

Barn.

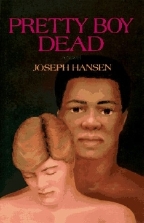

Oops.

Pottery Barn hasn't been invented yet, nor have cell phones,

and Tommy Hilfiger is still in his nappies. It's a lava lamp

and Mary

Quant

world, reflected in the cover images of his original first

editions, displayed in their full-size

glory in this gallery.

Hansen reflects the gay world.

Hansen's later books tackle more socially and politically

conscious themes, pornography in 'Skinflick', the AIDs epidemic

in 'Early

Graves', published in 1987, and the Vietnamese sub-culture

in 'Obedience'. He pulled Brandstetter from retirement in

the disappointing

finale,

'A Country of Old Men" in 1991. He probably shouldn't

have.

The smoking gun is ever-present in mystery fiction.

Hansen, while not widely read and certainly not widely promoted,

developed a loyal following among both straights and gays.

Did the Brandstetter

series open publisher's doors to gay mystery novelists? If

at all, certainly not wide, and certainly not with welcome.

Does

the Brandstetter

series rank with the best mystery novels of the time? Although

not unnoticed in his time, and not unheralded, probably not.

Hansen presented a homosexual as the protagonist, not the

sleazy villain,

in solid,

well written mysteries. Groundbreaking, but not earth shattering.

Did Hansen succeed in his mission to "write good whodunits

and right wrongs"? Absolutely, with honesty and old-fashioned

good storytelling and without stridency. And some thirty years

later,

he's left us with over a dozen novels, and a number of Brandstetter

short

stories, well worth reading, or re-reading.

While there's some chronological overlap between Hansen's last Brandstetter

and Michael Nava's first Henry Rios, there is a vast gap in

political and social climate. Michael Nava published his first series-novel

featuring Henry Rios, a gay, Latino, Stanford educated attorney

in 1986. Take Hansen and turn the dial up a few notches on

the intensity

scale, and you've got Nava. His setting is the LA of the 80's

and 90's, with race riots, police corruption, unrest, and distrust.

Toss

in Rios' strong Latino ethnicity and

you have a seven book series that was both original and timely.

Michael Nava, author of the Henry Rios Novels.

Since Rios is a lawyer, the whodunit stories are structured in

the Earl Stanley Gardner attorney-uncovers-true-circumstances-to-save-client

mode. (Sorry for all those hyphens.) Unlike Gardner's Perry Mason,

who seemed to sit around while others did the dirty work (off

camera),

Harry does his own dirty work, and often pays the physical and

emotional price. Like later Hansen books, Nava's novels tackle

contemporary

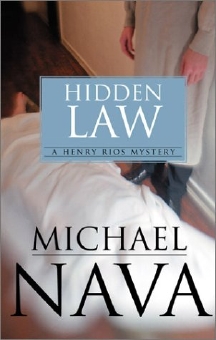

themes; political corruption between the haves and have-nots in

the Mexican-American community in 'The Hidden Law'; the secret

life of

a closeted gay Supreme Court Justice in 'The Death of Friends';

and the compelling and powerful finale in 'Rag and Bone', about

abused

parents and their equally abused children. Unlike Hansen, Nava's

stories most often focus on Latinos wronged, not gays wronged.

But like Hansen,

he penetrates not the underworld, but the ignored world of mostly

ordinary people living mostly ordinary lives who face peril, both

physical and psychological, by virtue of simple circumstance.

Nava's novels, like Hansen's thread dual stories. Nava's novels

are as much about Harry Rios, the person, as Harry Rio the "detective".

He writes compassionately and sensitively about Harry's strained

relations with his family, about his friends, straight and gay,

and about his

series of lovers. These are emotionally compelling stories,

heart rending, and searing, simple and right-on real. The whodunits

are well crafted and suspenseful, but Harry's personal connections

are

poignant and elevate the series beyond the constructs of the

basic

mystery genre. The action uber alles set will find little to

like here; physical violence and sleaze are present, but controlled,

and the narratives turn on the more troubling social and psychological

violence done to one person by another.

Michael Nava uncovers the Hidden Law.

Nava grew tired of his character well before his readers did.

Openly gay Henry was openly retired with 'Rag and Bone' in 2001,

the most

personal and complex novel in the series. Henry retired with grace

and dignity, leaving more than a few readers feeling like they'd

lost a good friend. For authors looking for ways to end a long-running

series that's lost its luster, (without killing off the protagonist)

look to Nava, who did it supremely well. Of course, finding Nava

may

be a bit of a challenge...he retired himself along with Rios and

has disappeared from the literary sub-culture.

Confessional personal stories and ancillary social agendas

can easily derail a good mystery - and the more intimate, emotional

or strident

they are, the greater the danger. Neither Hansen nor Nava

falls

prey. With skill, sensitivity and with their queer eyes

finely purposed,

they keep their stories on track and thread the personal

and social components so cleanly with the plot that they become

inseparable. Readers are rewarded with two series that are

compassionate and tough, innovative and satisfying, and, of

course, gay. All without Gucci!

|

|

| They did without. |