|

|

|

This Just In...News from the Agony Column

|

09-17-04: Time to Get Over the Cover; Who Let the Dog Warrior Out? |

||||||||||||||

Clyde

Edgerton Has 'Lunch at the Piccadilly' with Jack Riggs 'When the Finch

Rises'

But the name rang a bell, and knowing that I've shelved great stuff before for foolish reasons, I decided to at least take a glance at the novel. I opened it up to the Prologue. Some twenty minutes later, I had to rip the book out of my own hands and stop myself from going any further. As it happens, 'Lunch at the Piccadilly' (Ballantine / Random House, September 21, 2004, $13.95) is one hell of a funny, well-written and compelling novel. Even though -- and not just because -- it's a novel about a middle-aged man who keeps watch over his aging auntie when she takes up residence in a convalescent home. 'Lunch at the Piccadilly' starts with that Prologue I mentioned earlier, a wonderful little Q&A about how much it costs to set up your aging relative in a home such as Rosehaven Convalescence Center, where Carl Olive ends up placing his Aunt Lil. Edgerton hits every note of bureaucratic nonsense perfectly. He makes the absurdity of the situation comprehensible to those who have not been there. But that kind of thing is not hard to pull off, and I worried that the rest of the novel wouldn't live up to the rather dark-edged prologue. So I turned to page 1, 'Old People in Cars' and damn if Edgerton doesn't prove himself to be a simply great writer. He describes the process of getting an elderly woman (or man) into a car with such perfectly hilarious and heartbreaking accuracy that I literally could not stop reading. Readers might have twigged by now that I've gone through similar circumstances, and that is indeed the case. So when I say that it's clear that Edgerton knows whereof he speaks it's because I know whereof I speak. It's perfectly clear to me that 'Lunch At the Piccadilly' is a novel I intend to read and soon, probably in about a day. It's the kind of novel you can easily tear through. Anywhere you glance you'll find the conversations you can expect to have should you have a friend or a loved one in a convalescent home -- rendered with wit, charm and deadly accuracy, and surprisingly without smarmy sentiment. Yes, yes, that was what I was afraid of. That the writer would go for those Spielberg tear-jerker moments, and Edgerton stares the hard -- and much more entertaining -- truth in the face instead, time and time again.

And that is presumably the point, both of the pairing and of this column. If ever you see a novel that you think you might hate, give it a first glance, because you might actually find something you like. Even if the cover art is terminally cringe-worthy. |

||||||||||||||

Wen

Spencer's Serial Spree

Her latest novel, 'Dog Warrior' (Roc / Penguin Putnam; October 1, 2004; $6.99), finds Ukiah rescued from death at the hands of a religious cult by Atticus Steele, who proves to be Ukiah's long-lost brother. Ukiah is able to return the favor by virtue of his membership in a biker gang, the Dog Warriors. Atticus is involved in the distribution of a dangerous designer drug, meant to work on more than simple humans, certainly not an occupation for those who hope to live to a ripe and healthy old age. Apparently, however, one series of weird detection isn’t enough for this award-winning author. But I've got to admit that it's a bit of a surprise to see the usually military-minded Baen Book releasing 'Tinker', which looks to cover the women's side of the equation. Here we get the 18-year-old grrl genius who lives in a Pittsburgh that has been inter-dimensionally mixed with Elfhome. With a quick wave of the hand, elf magic is apparently a subset of quantum physics, and Tinker is a hit in both worlds. The publishers want us to see Buffy the Vampire Slayer "with a junkyard dog attitude". Well, one can hope. But clearly Spencer is on to a sort of series vibe with two publishers and a John Campbell Award. The panel we attended on this award seemed to come to the conclusion that it is occasionally useful to the author. In this case, is seems to have been both quite deserved and immensely useful to the author. Readers looking for a nice jolt of the supernatural-sleuth variety need look no further. Boy or Grrl, Wen Spencer's got you covered. Even if you've been raised by wolves. As a parent I can say that more children have been raised by wolves than one might suspect. |

|

09-16-04: A Closed System |

||||||||||||

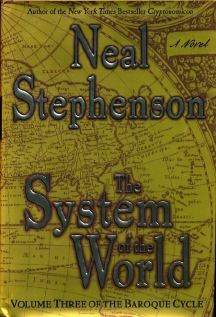

Neal

Stephenson Finishes The Baroque Cycle with 'The Systems of the World'

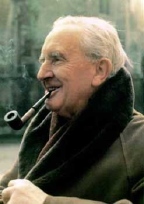

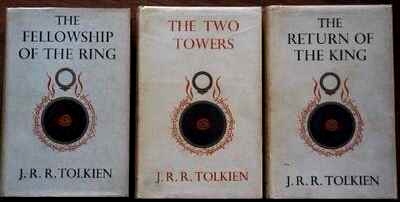

'Lord of the Rings' requires weeks -- or even months to read, and suggests to the reader that it should be re-read, and probably written about to fully encompass what Tolkien has done. In the light of many academic interpretations, many rather pale literary imitations, and a fine film adaptation, the depth and literary import of Tolkien's work has become unmistakable, even if you don't like it. And it's OK not to like 'The Lord of the Rings'. For all its import, it is rather dry, and all that complexity is certainly not appealing to every reader in the universe. I have to confess that thanks to over-zealous friends, even my appreciation of the books has been blunted.

In terms of scheduling alone, it's an amazing feat. For it was quite easily possible to buy the first novel when it first came out and simply read through the entire series, one after another, without much delay in between volumes, letting the accumulated impact build to the planned finale. Even had they come out at two year intervals, it would have been quite an accomplishment. By bringing them out so promptly, author and publishers have done the readers an impressive favor. But I think it will still be years before readers, writers, the literary community and indeed the world at large are able to unpack these novels and understand their import and their eventual impact. 'The Baroque Cycle' is probably the best realized demonstration of historical science fiction that we've seen and that we're likely to see. As we move firmly into the times that the Golden Age of science fiction first portrayed as "the future", there has been more and more whinging about the demise of science fiction. "How can we write science fiction about the future when we already live there?" is the cry. The answer, as found in these novels, is that science fiction need not take place or be about the future. Science fiction need not even deal with topics that one would consider "science". Science fiction, these novels demonstrate, is a sort of permutating look at the world, the creation of fractal literary patterns between events and concepts that can transpire in any time. Science fiction is not futuristic fiction. It's not even fiction about science. Broken down into its elemental particles, sfions, science fiction seeks to examine the secret clockwork behind reality, to make audible the tick...tick...tick... that moves us from one moment to the next. And in so doing, it will rock your world.

In the interim, readers can simply take heart that Stephenson and his publishers have allowed them to so quickly get a first glimpse of a vast new literary landscape. We get to rush out across it, unheeded, un-advised, ill-prepared. Our experience of this work will be utterly uninformed by the wisdom that will eventually be applied to these works. Nobody in the times that follow can duplicate the raw readings that we'll undertake. We may not experience the full impact of these works. But as literary explorers in an unmapped landscape, our experience will be unique, irreproducible. The impact they'll have on us, as readers will be immediate in an entirely different sense. We may miss the cultural information that will accompany age and analysis, but we'll have a personal vision of 'The Baroque Cycle'. It's unique, and it's ours and ours alone, each and every reader. |

|

09-15-04: Shape-Shifters Battle Tree-Huggers in New York; A Pleasure Boat Ride |

||||||

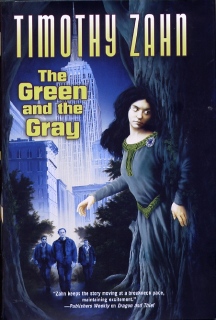

Timothy

Zahn's 'The Green and the Gray'

Timothy Zahn is probably best known at this point for his all-time bestselling Star Wars tie-in novel, 'Heir to the Empire'. Of course, lots of readers would hasten to say that Star Wars is science fantasy, not science fiction, and to my mind they'd be right. That would explain the science fantasy feel of his latest novel, 'The Green and the Gray' (Tor Hardcover; $27.95; September 17, 2004), which, with just a little tweak could easily fit into the urban fantasy genre as easily as it could science fiction. Unless you wanted to call it a mystery. That places the novel squarely in a no-man's-land that could, in theory send it to the NYT bestseller list. Here’s the setup. For seventy years, two feuding groups of aliens have lived among us in New York City. Refugees from a conflict they believe has destroyed their species, they maintain an uneasy peace, passing themselves off as humans but privy to advanced technology and unearthly powers. The Grays are shape-shifters, while the Greens have the ability to escape into trees. And they both have some pretty unsettling technology, which they intend to unleash upon one another when their conflict escalates from cold peace to a hot-headed war. Roger and Caroline Whittier are a troubled couple thrust into the center of this conflict. Only a cop and a former Ellis Island clerk are there to help them. Here Zahn offers up something for everyone, and it is the kind of book that has a potentially wide appeal. You get a toe-tapping police procedural mystery as officer Thomas Fierenzo investigates the attempted murder of an alien sacrifice, a heartwarming story of a family stitched from very disparate threads, hard alien technology and soft fantasy-creature aliens who would be perfectly at home in a trilogy of novels that include elves, dwarves and magicians. None of the latter, however, feature in 'The Green and the Gray'. Zahn writes smooth, slick prose that would be happy in a mainstream novel if it weren't busy with all these aliens, critters and mildly bizarre goings-on. I rather like the idea of a somewhat surreal urban science fantasy tale. It's Star Wars here and now, sort of. All-star artist Jim Burns painted the cover, and with the growing might of Tor behind it, Zahn might get to join literary luminaries like Janet Evanovich on the charts. All Tor has to do is to shape-shift the novel from science fiction into mystery long enough so that the chain stores buy up box-fulls and you've got bestselling genre-publisher science fiction. The question is: can this novel pass unnoticed amidst mainstream non-SF novels? It's possible that seventy years down the line, readers will point to this as the day that science fiction learned to live unnoticed midst the teeming fictional masses. |

||||||

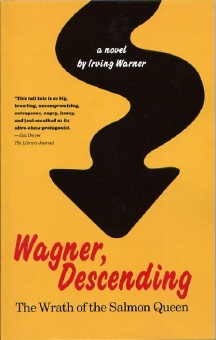

Irving

Warner's 'Wagner Descending: The Wrath of the Salmon Queen'

'Wagner Descending' is the story of Wagner, an obese, foul-mouthed heir to billions locked up in a fat-farm from which he escapes on a cross-country journey to eat his way back to sanity while escaping the clutches of the Salmon Queen, his unlovely mother who had him put away in the first place. Now while this novel is anything but slick and easy, it's actually pretty easy to read, that is if you enjoy a non-stop narrative filled with profanity and food. You get ranting mania about Fatty Arbuckle, steam-powered catapults to launch non-violent melons into enemy greenhouses, angst molecules and "the only positive effect of a 430 pound man, naked save for boots -- standing dazed on a secondary highway." 'Wagner Descending' does itself a number of favors. Short chapters, lots of great jokes and wonderfully creative cursing, and only 239 pages total. Of course, it's not a book for the entire world. Not everyone finds the same humor in foul language that I do. But for me, cursing beautifully is a highly prized and all-too-rare art-form. In 'Wagner Descending' you'll find a paragon of blasphemous prose, with enough plot and character to keep you more than interested in what happens between blasts from the oath-factory.

I suspect that 'Wagner Descending' might have a much wider appeal than one might anticipate. That, packaged differently, and publicized from New York, it could as easily be a bestseller as anything else out there. But as long as it sells to readers who enjoy it, it's done it's work. And if it shows up on any bestseller lists, if it gets incorporated into the mainstream, then I'll have to start digging again for something even stranger. But a brief investigation suggests that Pleasure Boat Studio might be an excellent place to start.

|

|

09-14-04: 20 years of Cyberspace |

||||||||||

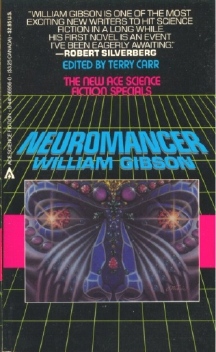

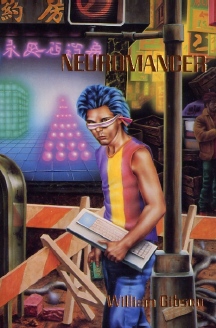

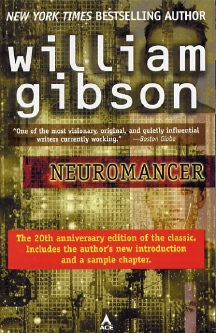

William

Gibson's 'Neuromancer' Gets a 20th Anniversary Edition

This was the novel for which he coined the word "cyberspace", a novel that, like the movie 'Blade Runner' seemed to embody the chaotic future for which we were headed. Gibson's vision of keyboard jockeys and mercenary women assassins, a polyglot multi-culture where the ultra-rich and the virtually destitute share the same mean streets and sidewalks, is still in our future. But in the interim, we've done all we could to make his world come alive. So yes, I bought but gave away my cheesy paperback copy of 'Neuromancer'. The idea that paperback books might actually accrue value seemed ridiculous to me then. But by the time the first US hardcover edition came out in 1986, I was lining up to buy it at the old Change of Hobbit bookstore on Santa Monica Boulevard. A skinny young man was there to sign them, and I got mine duly signed, in a looping, legible script. When I saw that the edition was from Phantasia Press, I was rather surprised. I was already quite interested in buying limited and small-press editions of books by 1986, and I'd seen plenty of Phantasia Press titles that had left me underwhelmed. I was uninterested in the work of either David Brin or C. J. Cherryh, and those were the authors I'd seen most often under the PP covers. So I was glad that Phantasia had started to publish something other than what I considered warhorse science fiction. My interest in the genre was just about gone and Gibson was one of the last SF authors I was particularly interested in for many years, as I read through the growing canon of horror fiction until that genre drowned in its own waste. With the Phantasia Press edition a new Neuromancer tradition was born. That's the patented William "I wrote this on a typewriter" Gibson introduction. But the most salient quote is that with which he concludes the introduction.

Obviously that was not meant to be. 'Neuromancer'

is clearly one of the genuine survivors, and specifically for the reasons

elucidated in the

first introduction.

Not because of how well it anticipates this world. Gibson himself points

out in his latest introduction that he failed to presume mobile phone

tech, and like Gibson, I think one of the most powerful images in the

novel involves "the

sequenced ringing of a row of pay-phones". No, the reason that

'Neuromancer ' will survive is that it speaks so eloquently of the

world as it was

then, in 1984, as it is now, in 2004 and as it ever will be. Bright,

dark, shiny,

dingy, a confusing complex admixture of opposites stirred together

but not mixed really, just shoved side-by-side in an increasingly shrinking

space, more and more people, less and less of everything else. Messy,

unplanned, improvised, and yet, somehow, just once in a while, strangely

and eerily

beautiful. |

|

09-13-04: Women in Mystery; Fantasy & Science Fiction Turns 55; Joanne Harris Rises Again |

|||||||||

A Conversation With Laurie R. King and Marcia Muller

Both writers were kind enough and enthusiastic enough to consent to my request for a conversation on this subject, and last Thursday I sat down to talk with them. You can hear the interview broadcast from KUSP on September 20, 2004, at 10:30 AM. Or you can download the files now, in either MP3 or RealAudio formats. Here's an excerpt from an email I sent the two writers before the interview. "On Aug 24, 2004, at 6:31 AM, Laurie King wrote: The result exceeded

all my hopes. The three of us sat down and talked for a solid 55

minutes on a variety of subjects. Both writers were

quite well prepared; you can hear Laurie R. King rustling her notes.

Most importantly, the writers responded to one another's comments.

This is true dialogue between two of the best fiction writers you're

going to have the pleasure of reading. I'll be publishing my reviews

of both their latest novels later this week. I'll be reading a lot

more work from these talented writers. There's a backlog of 22 Sharon

McCone novels by Marcia Muller and 12 novels by King that I've yet

to read. This is one of the greatest rewards of exploring new writers.

Suddenly, a whole world of totally enjoyable reading opens up before

one. And that's what reading and reviewing are all about. With the

insights these authors share, the reading experience is even more

involving and intriguing. |

|||||||||

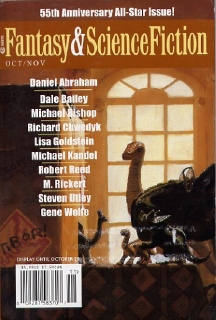

Young Writers and A Vigorous Middle-Aged Magazine

In his latest rant, he talks about how mind-bogglingly hard it is to crack into the world of selling short stories to professional markets. He talks about a writer he calls "Norbert" who, upon having a story that Gary liked rejected by the Borderlands editors, goes off on a rant of his own, about how his best story was rejected and it seemed like you had to know someone to get something seriously considered. Braunbeck's response is as entertaining as you might hope it to be, and is likely to cause his site to end up in your bookmarks list.

And the

result of following that advice is that you may get published. After years and years. Be patient. Perfect your work.

In fact, many of the writers in this issue of F&SF

are to a certain extent "new" writers. Daniel Abraham,

M. Rickert and John Morressey are not household words -- yet.

But if they continue to follow Heinlein's rules, they'll certainly

increase their chances.

That's nearly a novel between

Goldstein and Wolfe alone. Dale Bailey, who has 'The

Resurrection Man's Legacy', a

recent

short-story collection out from the ever-dependable Golden

Gryphon Publishing, here recaps "The End of the World

as We Know It". Steve Utley managed to make F&SF

unfurl their footnote font in "A Paleozoic Palimpsest".

If you don't subscribe, you may want to swing by your local

independent bookstore to pick up a copy. Stick around for

the rest of the stars, including personal favorite and editing

legend Michael Kandel, who did the world a great favor translating

Lem, and according to his brief intro, is currently translating

an anthology of Polish monster stories. That is a project

I plan on finding out more about. |

|||||||||

| Black

Swan Re-Issues Sleep Pale Sister by Serena Trowbridge

When I met her she talked about the influence of Gothic literature (see column) and how she had once hoped to single-handedly rejuvenate this genre. Sleep, Pale Sister is heavily influenced by Victorian fiction such as Dickens and Wilkie Collins, and draws heavily on the Pre-Raphaelite movement. At the time, she says in her foreword to the new edition, it “sank without trace”, which is perhaps a slightly harsh comment, but certainly people are much keener to read it now that she is famous for other novels; but don’t expect food and sunshine here.

|