|

|

|

This Just In...News from the Agony Column

|

03-10-06: Colson Whitehead Knows That 'Apex Hides The Hurt' |

|||

"He

came up with names."

Heck, anyone should know the power of names, mystical or otherwise. Depending on which version you're talking about -- Protestant, Catholic or Hebrew -- it's the second or third of the Ten Commandments. "Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain." Rating high in the commandments, one presumes, suggests that the issue is of some importance, and of course it is; names define that which they name. Colson Whitehead knows about names, which is why you just have to love his latest novel, 'Apex Hides the Hurt' (Doubleday / Random House ; March 21, 2006 ; $22.95). That is a title guaranteed to grab at least my intention, and being the name of the book, it should tell us more than a bit about it. Hmmm. But then, perhaps Colson Whitehead knows that names can be used to hide as much as they can be used to reveal, no? Whitehead is the author of two novels -- 'The Intuitionist' and 'John Henry Days', and a collection of jazzy essays titled 'The Colossus of New York'. I talked to him back when the latter work came out and asked him about this novel, but like many writers he was loath to talk about an unfinished project. In fact, he described the book tour itself as means of procrastination, and we then launched into a discussion of writers' superstitions. And if it seems strange that I wind up talking about genre fiction and superstitions when talking about a very literary, MacArthur and Whiting award-winning literary author of noted works of fiction such as 'The Intuitionist' and 'John Henry Days', well, that's because to my mind, Whitehead takes a rather science-fictional approach to literature. Even though he writes only about the here-and-now, he approaches our world as if he were visiting from another world. He manages to get far enough outside of the cultural ambience of American life to view it with the objective eye of a scientist. You might think he'd ask you for a sample of something. His latest novel takes the same outsider approach. 'Apex Hides the Hurt' is about an out-of-work nomenclature consultant. A namer of names. Who, of course, is likely to remain nameless in Whitehead's unusually objective universe. The novel begins as Our Nameless Hero loses a job under circumstances that remain mysterious. But he's soon on a new gig, called by the citizens of Winthrop. It seems that a software mogul wants to change the name of the town to something that will attract business, citizen, money, movers and shakers. Chicka-boom! Instant progress! Renaming the town is after all the best way to re-build the town. Heck you can get yourself a nomenclature consultant and few road signs for a whole lot less than even the environmental impact study required to build that new mall. And once you have the new name, the money comes to town. Blink and the new money is footing the bill for the new mall. Oh, the power of names. Of course, none of this proves to be as easy as anyone is led to think it will be. In naming the town, Our Hero is also unnaming the town. Isn’t it always that case that what makes some people happy will make others unhappy? But the unhappy are no less able to act, to speak and to try to sway the opinions of those around them to the point where they’re no longer unhappy. Whitehead's latest novel has the same bureaucratic, slightly surreal edge to it that his first novel, 'The Intuitionist' had. It's short, barely topping out over 200 hundred pages, and inclined to be funny. Whitehead is a great comedian, since he takes everything so seriously. Only when you buy your own premise can your jokes have any heft, and Whitehead not only buys his own premise -- that names matter -- he's easily able to sell it as well. From there everything flows in the usual direction -- downhill. Some waves are worth riding and others are worth avoiding. The downhill wave is generally of the latter variety, unless you happen to be on top of the hill. Then you can watch as others endure the consequences of your actions, as those you've named live up to their names. No matter what, it's always best to see the wave going, not coming. If you're looking for some imaginative and incisive observations of our peculiar nation in our peculiar world, then Colson Whitehead is a man you want to listen to. He'll provide you with a perspective that's just off enough to reveal shapes and shadows that might not otherwise emerge. I don’t think he's an alien of course. But when they arrive, maybe he should be sent to meet them; or at least, allowed to name them. |

|

03-09-06: George Zebrowski's 'Macrolife' |

|||

Where

Have All The Utopias Gone?

Make no mistake about it, I'm all for excitement, but it can come in many forms. Zebrowski's 1979 opus harkens back to the science fiction of writers like Arthur C. Clarke, Olaf Stapledon and Stanislaw Lem. It was written before the age of video games, and that makes a huge difference in the very temperament of what Zebrowski was doing. 'Macrolife' is a novel of ideas in the most classic sense of the term. Zebrowski asks big questions, offers big answers and examines a sort of utopian ideal that doesn't get much play in the our post-Pong world. Given this, 'Macrolife' does not stint on the big bangs, either. The novel begins as the Bulero family brings about The End of Life As We Know It. Before you can say, "Damn, the world is ending!" the world ends in a bang, not a whimper. Humans are forced out into space in a manner that offers Zebrowski the opportunity to create his vision of a powerful, productive future for humanity. This is the "mobile utopia" idea, the "macrolife" of the title. It incorporates elements of lots of classic science fiction novels, the kind of stuff that many readers will remember with a fondness and poignancy that seems pretty rare these days. I don’t know about you, but I can slip right back into my pre-teen self, reading James Blish's 'Cities in Flight' and Arthur C. Clarke's 'Childhood's End'. There was a powerful combination of joy and intellectual rigor in those novels. Characters lectured one another, or read primal sources that lectured directly to the reader. Ideas drove the action. One of the ideas that drove the action, and that drives the action in 'Macrolife' is the concept of a utopia. The ideal society has been a standard of science fiction since Plato first conceived of it in 'The Republic', and yet we've not seen a lot of utopias of late...or have we? Paired with Zebrowski's vision of an ever expanding human intelligence at large in the universe in 'Macrolife' is Keith Brooke's 'Genetopia', David Marusek's 'Counting Heads' or even Cory Doctorow's vision of the Bitchin' Society in 'Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom'. As conceived by Zebrowski, a utopian human existence was seen as rather pacific, even if there were infinite adventures to be found. But the utopias our current science fiction writers offer us are more chaotic and less, well, pleasantly calm. What we're seeing is no less than an evolution of utopian thought, one that may loop back on itself. I find it fascinating that a single imprint from a single publisher offers the whole spectrum in the space of a couple of months. This is a tribute to the genre as a form that has achieved a level writing competence where older works are seen to have worth even if the technology or the concepts behind them have changed. That's no surprise. We've changed, but we're still no less attracted to the vision that Zebrowski offers. Brooke's chaotic world of genetic engineering, Marusek's world of clones and AI, and Doctorow's vision of plenty speak as much to the "twisted mirror held to the present" (a phrase that Doctorow spoke during my interview with him in San Francisco what seems like ages ago) as they do to our evolving concept of utopia. 'Macrolife' is more than a vision of our possible future. It's also a vision from the Cold War, from a time when it seemed as if two monolithic powers would struggle forever. But now our concept of utopia has moved on a bit. We're so used to hustle and bustle that we expect our ideal societies to supply both, albeit in pleasurable forms. Indeed, what was once dystopian -- the world of enforced consumption offered by Frederic Pohl in 'the Midas Touch' -- now seems a good deal more utopian to our consumer-charged lifestyle. The utopias of years past threaten us with boredom. Indeed our utopias exist in a sort of quantum state. One second, they are a wave of perfection, then next a particle of chaos. Good or bad? Some of us already lead a utopian lifestyle. Others see our world as incurably dystopian. Who knows what forms tomorrow's utopias will take? As David Bowie once wrote, "We've got five years." Getting back to the part that's important for those of us in the present, 'Macrolife' is also an example of why Pyr has a bright future. It's a $15 trade paperback with the usual to-die-for cover by John Picacio and the original illustrations by Rick Sternbach. There's more than a bit of irony in that. Watson's introductory rant really gets up a head of steam when he starts talking about the *.* franchises and their deleterious effect on the science fiction genre. I heartily agree. But the original illustrations are from a man who won an Emmy and was the "Senior Illustrator/Designer" for Star Trek. It only goes to show that science fiction is a lot more complicated as a genre than either its detractors or supporters might believe. Everything connected, everything different, everything is the same. Five years -- that's not a lot. Five years! |

|

03-08-06: Christopher Moore is Doing 'A Dirty Job' |

|||||||

Death

Takes a Pratfall

But we know that Chris Moore is actually pretty much way beyond bold. You don’t write a novel about the "lost years" of Jesus unless you're willing-to-have-stuff-thrown-at-you bold, but 'Lamb' is one of the bestsellers mentioned on the dust jacket of 'A Dirty Job'. Moore has, in fact, pulled off the rather difficult feat of making a career writing humorous horror. That too, is a dirty job, and his readers are glad that he's up to the task. The whole "dirty job" idea might very well be the genesis of Moore's latest novel. Death and comedy do go hand in hand. Both are universal, though death is rather more common. This is unfortunate, and Moore is doing his part to correct the imbalance. In 'A Dirty Job', Beta Male Charlie Asher is there the moment his daughter is born. He alone sees the guy in mint-green golf wear at his wife's bedside. This proves not to be a fortunate vision. From that moment forward, Charlie's life gets more difficult -- comedy difficult, to be precise. But helping Charlie to make that difficult comedy so much easier is Death, and lots of it.

Well, the answer is that you have to love such a novel, even if it has been done before. And by some significant talents. Let's see, there's Terry Pratchett's 'Mort', which introduced that beloved guy WHO ALWAYS TALKS ONLY IN CAPITAL LETTERS. There's Neil Gaiman, who has made a fairly big deal of death in his Sandman comics. There's the lesser-known (but quite good) 'Damned If You Do' by Gordon Houghton, which I just managed to extract from the bookshelves behind the file cabinet. I reached blindly to pluck that book from where I last remembered it being, and I can tell you, it's been a while since I last checked this one out. But when all is said and done, there's always quite a bit you can say about Death. I mean, he's a busy guy. A dirty job -- sure. A boring job -- never. Personifying death, of course, gives us something to rail against, and personifying death in a comedy, well, that gives the writer the opportunity to think up all sorts of delightful Rube-Goldberg-style mayhem. But what Moore does best is a wonderfully deft combination of comedy and character. All the death in the world won’t evoke a single snort of laughter unless you care about the people being run over by a train, hit by a bus, or hanging out underneath that plummeting piano. Moore's novels all feature middle-class, average Joes, carefully created so as to emphasize the humor that dots the I's and crosses the T's of our everyday lives. Moore clearly loves the folks he's writing about, and so do we, even if they’re sometimes kind of well, either a) inept [actually: especially if they’re inept] or b) bad. For inept, let me take this opportunity to mention the title character of Moore's previous novel, 'The Stupidest Angel', now available in a beefed-up Version 2.0. Azrael, whom we first met in 'Lamb', comes to earth to answer a Christmas wish. "Bring back Santa," the child pleads, and Azrael answers that wish. Oops. Santa was a dead drunk, uh, literally dead. And thus is what is arguably the best novel ever written about a Christmas zombie invasion born. Not surprisingly, it only took one Wise Man to write it. But he did need the help of the inept! We don’t have many chances to laugh at ourselves, and fewer chances to literally laugh in the face of death. As one who generally avoids leaping from roof to roof in the pursuit of master criminals, as one who has found a distinct absence of car-flipping chase scenes in one's life leads to advantageous insurance rates, I find myself faced a dearth of opportunities to engage in laughing at Death. 'A Dirty Job' offers that and more. Moore uses the word "fuck" in a humorous manner. And so we must read him. If dying is easy and comedy is difficult, then using the word "fuck" humorously is a rare and precious thing. We must have our standards! |

|

03-07-06: Bringing Up 'Brainchild' |

|||||

Four

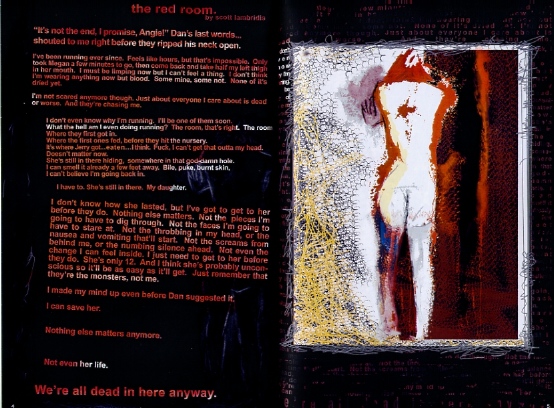

Color Slick Sick City

For all the different theories about why we both love and fear zombies, my take is that it's the old fear of infection. You know, when someone consumes your bodily fluids by chomping into your, say, arm, that's not only going to hurt, it's going to get infected. And with an aggressive, flesh-eating disease vector, things are going to spiral out of control pretty quickly. Then you're down to part two of everybody's favorite nightmare: The Zombie Apocalypse. And I'm all about zombie apocalypses, because the first wave, David Wellington's 'Monster Island', led me directly to the second, 'Brainchild: A Collection of Artifacts' edited by Scott Lambridis. (Omnibucket ; March 1, 2006 ; $15.00). This super-limited edition anthology, with a first printing of 250 copies, is as easy a must-buy as anything else you're going to stumble across on your way to consume thy neighbor. It's cheap, it's gorgeous, it's disturbing as all hell. In fact, it's so nice, I'd venture to say that even were I to be infected, afflicted, in between bouts of consuming the living flesh of my neighbors (and I'm as afraid of them as they are of me), I'd still be able to pull together the brain cells to pick this one up. I guess it comes as no surprise, or should come as no surprise, that buying this zombie anthology is something of a no-brainer. Let me here note that the copy I have suggests there won’t be a lot of chances to do so; it's 150 of 250. There are potentially only a hundred lucky brain-eaters out there. I have to admit that you won’t need many working neurons to enjoy 'Brainchild'. It purports to be a "collection of artifacts", an after-they-left-their-napkins-behind dessert to a flesh-eating, civilization-consuming plague of zombies. As such, there are not a lot of words and there is a lot of graphic design. Apparently, only great designers and unknown artists will be left uneaten in the upcoming ZA. Yes, the designs are matched with words of equal splendor, but there aren't so many of them as to require an uninfected brain to read this book. 'Brainchild' is a beautiful but sick, gory but slick.

Not to be taken lightly is the care, the precision and the beauty that has gone into designing and printing 'Brainchild'. It's drop-dead gorgeous from cover to SCREECHING HALT Back two pages of entirely-differently designed advertising Cover. You’d think that the company printing and advertising would have looked at the rest of what’s there and thought, "Hmmm...harmonious is better, yes? Let's be in harmony here." They didn't, but it doesn't detract too much from the rest of the piece. In a sense, it's the most shocking image here. The rest is so drenched in beauty, in our-time-has-passed-please-pass-the-human-forearm ennui that coming back to the reality we inhabit is something of a shock. But that only emphasizes the delightfully dark artistry of the rest of "Brainchild." "Brainchild" is the brainchild of Scott Lambridis, I'm pretty sure, and it comes from this Omnibucket Publishing that suddenly jumps into the spotlight. They've got some great work coming out, and if you’re lucky, the website will be faster for you than it was for me. Once it all gets loaded up, it's very, very nice. You might require the patience of a moldering piece of human flesh, the kind of chunk left behind when those around you have been eating one another but ignoring the most basic table manners, to actually read the verbiage on the website, but the sneak-peeks look very encouraging. Assuming, of course, you find dark art encouraging. I know that many of my readers come here to find out about really weird little items that aren't going to get a lot of play in the newspapers, or get selected by a morning talk show running a reading club. This is not reading club material. This is club-from-a-human-forearm material. If you’re interested in the latter, if you love beautiful little oddball books, then you owe it to yourself to pick this one up. I guess there's not a lot of meat here, in a sense, but what there is, is utterly delectable. Think of it as being the prose equivalent of baby back ribs. Need I elaborate? I didn't think so. |

|

03-06-06: Ray Kurzweil Warns 'The Singularity is Near' ; Kim Stanley Robinson Podcast |

|||

Look out!

That being the case, get yer wheelbarrow. The gist of Ray Kurzweil's new book about technology is the both the Great Love and the Great Destroyer of current science fiction. That would be the "Singularity", to wit, (and here I quote from this book): "It's a future period during which the pace of technological change will be so rapid, it's impact so deep, that human life will be irreversibly transformed...This book will argue, however, that within several decades information-based technologies will encompass all human knowledge and proficiency, ultimately including the pattern recognition powers, problem-solving skills, and emotional and moral intelligence of the brain itself." Yes, all this and about 651.8 pages more. So who should read this book, or at least buy it? Well, just about anyone who is interested in cyberpunk science fiction will find this a pretty compelling and certainly well-organized look at the implications of the technology that you've read about for the past twenty years. If you're interested in writing science fiction, of just about any stripe, this book would be a wise ground for finding and re-fining your concepts of the what the tech can and might be able to do. If you just want to read a lot of science fiction that is really mind-bendingly wonderful, for example anything from Vernor Vinge (the first SF writer to coin the term as we know it today, though not the first to come up with the concept) to Charles Stross -- in particular his 'Accelerando' novel/sequence/whatever-you-want-to-call-it. Cory Doctorow and John Meaney come to mind as well. And loads of others, too many to name without spending more time on the fiction than on the facts, or the fact-based speculations of this book. So, let's see; SF readers and writers, so far. Technophiles of all stripes, but then, if that word accurately describes you, then the chances are you're either reading or writing SF. So -- technophiles, check. SF readers, check, SF writers check. Current event and business junkies will find a lot to like here as well, though the last time you saw this many graphs embedded in the text was when you read the Crichton novel 'State of Fear'. Parents might want to give this one a spin, just to get a vague idea of what your kids are in for. Even if none of Kurzweil's trendspotting proves to be accurate, you'll have an idea of what everyone at least thought as going to come down. I guess the short answer to the who should read this question is, well, just about every conscious being. Kurzweil divvies things up pretty logically; he starts talking about 'the Six Epochs' (periods of history and scientific development), then offers 'A Theory of Technological Evolution: The Law of Accelerating Returns', then a look at 'Achieving the Computational Capacity of the Human Brain' (hardware to emulate the human brain), follows that with the uber-logical 'achieving the Software of Human Intelligence: How to Reverse Engineer the Human Brain', and goes on to cover 'GNR: Three Overlapping Revolutions' (that would be genetics, nanotechnology and robotics/:strong AI). Then you get 'The Impact' and Kurzweil's declaration that "Ich bin ein Singularitarian". OK Ray! He wraps it up with 'The Deeply Entwined Promise and peril of GNR' (remember, genetics, nanotechnology and robotics/:strong AI) and a lengthily pre-emptive 'Response to Critics'. All this meat is followed by over a hundred pages of notes and an extensive index.... Which I perused long enough to note that Kurzweil goes on very little about the subject that's near and dear to me, that is, reading. Yes, because in this post-Singularity world, in theory, well, uh -- you no longer need to read. You can punt all the rest of the scary stuff, that in itself is enough of a stopper for me. And it piques my interest in brain studies about reading, for both the peculiar and deep pleasure it provides but also for the how it changes the brain. Because we know that reading does change the brain, and uploading the same data cannot offer the same experience. Presumably, since 'The Singularity is Near', I won’t have to wait too long to find out what the deal is with reading afterwards. Because in a sense, I'm sort of a plant-gathering enthusiast talking up the thrills of looking for edible veggies in the times shortly before agriculture. It's odd, but yes, I know that as a science fiction reader, I'm working and hoping for the demise of that which I enjoy so much. Here's to an end to readi |

|||

"It is a kind of a bad science fiction scenario that we live in right now."

If anyone does want the second half right away, you can email me. In the interim, here are live links to the MP3 and RealAudio files for part one. Let me assure you that Robinson is a wonderful speaker. He's got a great speaking voice, he's very funny and his material here is top-notch. We started out the conversation talking about the generalities of global warming, and ended up in the first half, at least, talking about 'State of Fear'. If you've never heard Robinson speak, then prepare your checkbook. You'll be wanting to buy something, anything by him afterwards. You'll be thinking that anyone this entertaining in a recorded interview is bound to be utterly compelling on the printed page, and you'd be completely correct. |