|

|

|

This Just In...News from the Agony Column

|

08-11-06: S. M. Stirling Brings 'The Sky People' to Earth – and Venus – and Mars |

|||

The

64 Kilodollar Answer to the Dime - A - Dozen Question

See, I have made a difference in your lives, haven't I? Now let me do so once again. Let me bring back the fun, the joy, and no small amount of introspection into your lives. Let me suggest that you order in advance S. M. Stirling's 'The Sky People' (Tom Doherty / Tor ; November 14, 2006 ; $24.95). Stirling is justly well-known as one of our premiere purveyors of alternate history. His novel 'The Peshawar Lancers' was such an absolute hoot that I was dragging it around for months pawning it off on unsuspecting but happy-once-they-read-it reading buddies. What Stirling excels at doing as a writer is very interesting in a strictly literary sense, and when he gets on right on the bead he's well-worth a pre-cleared space in your reading queue. You're getting this warning a bit on the early side, because I know your queues are full, but heck, everyone deserves a book as rewarding as 'The Sky People'. In just world, which this is demonstrably NOT, this would be an instant bestseller and directors would be falling over themselves to get the screen adaptation rights. But this is the world we have, and at least it is generous enough to cough up a decent novel now and again. This particular much-more-than-decent novel, like many in the busy subgenre of alternate history, spins from a specific idea. But Stirling is a man capable of great leaps of the imagination, and the idea behind 'The Sky People' is most assuredly not one of the dozen or so you can get for dime at any science fiction convention or indeed, whilst gazing at the alternate history shelves of your local bookstore. What Stirling has said he tries to do with his alternate history concepts is to provide himself a space to create the most exciting writing and reading space available. In 'The Peshawar Lancers' he talked about this. The earth is completely explored. If you want to write a H. Rider Haggard-style story about adventurers, well, where can they go? Azusa, California? There's just not a lot of earth there to adventure about in. I know, I know there are spaces, but not Haggard-Burroughs-sized holes in our understanding. The same goes for the solar system. Alas, you have to get underneath the frozen moons of the outer planets before you can even hope to have much of entertainment value. The lush jungles of Venus, the fertile deserts of Mars, they're long gone and replaced by the harsh, unforgiving and worse yet – kind of dull landscapes we've seen via the various crashers and landers for the past forty-five or so years. (And understand, that I'm as thrilled as heck when we see them drive around these places, but you know, it's not Barsoom.) No, no hope for adventure there, right? Enter S. M. Stirling. In 'The Sky People', those landers of the sixties found not the arid boredom-scapes we know so well. They found the lush worlds of pulp science fiction brought to life. Volcanoes. Jungles. Dinosaurs. Y'all come back now, y'hear? Oh, of course we come back to that kind of scenario. None of this lollygagging space exploration in Stirling's vision. Nope, as the novel starts it's 1988, the Cold War is hot, and the only things hotter are the bearskin-clad vixens of Venus. The US and Russia have both established bases there. It's a wild and wooly frontier. Marc Vitrac has just been assigned to New Jamestown, and he's rarin' to go. But you know, it's kind of odd how closely these Venus humans resemble Earth humans. And the beast men, why, they're just like Neanderthals. What’s up with that? This isn't just parallel evolution. Something did this. Something a quite a bit more competent than humans. So this is how Stirling creates for himself a wonderful little puzzle to write his way out of as well as the potential for kick-ass, high-adventure. This is a writer using the literary form of science fiction to create for himself more literary potential. Just as sentences and paragraphs are tools of the writer, so too, can genre be a tool for the writer. But even the most brilliant ideas need to be executed. This is where Stirling excels. He knows how to write to the level of his concepts. Since he's creating the potential to write a great adventure story, he writes a great adventure story. But he also manages to naturally work in some pretty keen observations about the real world into his invented one. Mapping between the two realities becomes of the great joys of reading his work. Well, that, and dinosaurs chasing bearskin-clad vixens on Venus. |

|

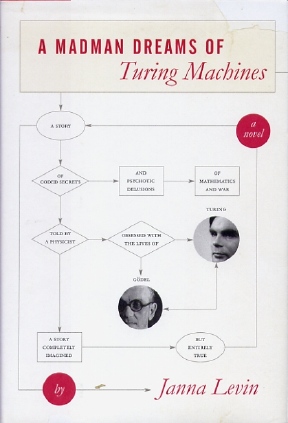

08-10-06: Janna Levin Knows 'A Madman Dreams of Turing Machines' |

|||

Science

Fiction, Yes, Sci-Fi, Not Really

No fighting now! Calm down, you know we love you. And as you stare at the "SciFi" section in the local chain bookstore, row after row of cover illustrations just this side of cheesy, well, you might be tempted to hear strains of Elvis singing, "...in the ghetto–and his mama cries..." Oh my. And, then another snippet of music might come to you: "Is that all there is?" Well, of course not. Lots of folks are out there writing science fiction who aren't in Da Club, not because they’ve been excluded so much as they never got round to thinking of themselves as being part of Da Club. But how else could you describe the recent book by Adam Felber, 'Schroedinger's Ball'? I mean: fiction about scientists. Not a big leap to being: science fiction. Weird and funny to boot! And now we have Janna Levin's 'A Madman Dreams of Turing Machines' (Alfred A. Knopf / Borzoi / Random House ; August 15, 2006 ; $23.95), yet another entry in the probably-doesn't-want-to-be-labeled-as-science-fiction sweepstakes despite the fact that it is: a)fiction, b)about scientists c) [bonus round] about scientists who are of particular interest to Da Club. The point being that you'll have to travel beyond the confines of the *.* section to find this little gem, and in fact you may or may not be likely to consider it a gem. Your ability to be inclusive as opposed to exclusive will be directly proportional to your ability to tolerate novels that involve no speculation beyond that of trying to get inside the minds of scientists who have alas, long ago passed from this veil of tears. 'A Madman Dreams of Turing Machines' is a peculiarly potted dual biography of two of science fiction's more (if not most) influential icons, Alan Turing and Kurt Gödel. From a sort-of non-partisan, ex-English major point of view, this is pure science fiction. But it would never rate as SciFi, essential or otherwise. That's fine. But let's give it a test drive, shall we, just to see what’s under the hood. Mosey on over from "in the ghetto" to the literary section of the bookstore, pick it up, and you'll get, to my mind a cover to die for. Jacket designer Peter Mendelsund pretty much lays out the novel for you in a flow chart–no spaceships required. What Levin, herself a scientist, has done is to imagine the lives of Gödel and Turing, based on extensive research and an obsessive interest. The result is pretty startling, and quite compelling, highly imaginative but not in the "creating a world" way. No strike, that, Levin does create a world, in fact two worlds, the inner worlds of Turing and Gödel, as fascinating as any Middle Earth, Dune or whatsit universe we've ever seen. Worlds in this case, dominated by tormented sexuality, caffeine-driven intensity, world wars that we cannot not now competently imagine. Levin fearlessly faces the facts of both men, their shortcomings as well as their remarkable accomplishments, each throwing the other into a new perspective until her chiaroscuro of perspectives becomes so complex that the lines become threads, the threads become a whole cloth that you've not seen before. Naked singularity. Incomprehensible, yet utterly understood. Levin holds two contradictory thoughts at arm's length, and the reader can't help but be fascinated. Levin's backed her book with a boatload of notes, and as the author of: 'How the Universe Got Its Spots', she's surely well-qualified to venture right into the world of science fiction. The real hope is that science fiction readers will embrace the sense of adventure that enables them to read the genre in the first place and venture beyond the boundaries of time and space, into the literary world. Here's a book about our heroes, by a new hero. Set it next to Felber's silly-but-smart 'Schroedinger's Ball', and wonder if the future of the genre lies in the past of science. Let's celebrate Levin's and Felber's work, their oh-so Science fiction. |

|

08-09-06: Justina Robson Unfolds the 'Mappa Mundi' for Pyr |

|||

Let

me look into your brain

'Mappa Mundi' is now, frankly, a very different book for me. Back in the day, when I first read it, I was still a bit more of a casual reader. I wasn't yet in the habit, at least, of reading with a stack of stickies. The net effect of this change in reading habits is that I'm quite a bit more enamored of dense, dark writing, and 'Mappa Mundi' has that in spades. 'Mappa Mundi' is about the pre-singularity mapping of human thought so that it can not just be understood, but controlled. Given my recent conversation with author Steven Kotler about the science behind spirituality, it's clear we're well on the way to the mapping aspect, and especially with regards to schizophrenia and madness. And once we cure the sick, we will certainly need to cure the healthy–of any thoughts that might compromise our National Security, right? Add to that my conversation with Vernor Vinge who gives a frightening portrayal of what he calls YGBM – You've Gotta Believe Me – technology, and this novel takes a left turn at science fiction and heads well into techno-horror territory. Mind control is always well intentioned, until you're on the receiving end. Well, that's the fear, and it's clearly a fear we need to keep close to hand. Robson's novel, set in the post-present, plays on that fear well. Robson excels at creating compelling mystery plots with characters who spring to life in the book-reading part of your brain. Her books stay with you long after you read them, and 'Mappa Mundi' is no exception. What she brings to science fiction is some of the writing style I associate with P. D. James, a rather lyrical but dark vision, even if, as in this novel, she's writing about high-tech horror. There's none of the hollow slickness usually associated with that genre here. In fact, I recently looked at a novel that seemed quite promising in premise, and rather similar. But the writing was to my mind rather bad, and I never even bothered to read it. I put it down after reading a few pages a few different times, slipped it out of the queue and quietly off the shelves. Where that novel was utterly uninspiring this one gets me to the keyboard writing, even though I first read it over four years ago. That's why I do this column, to write about books that are worth my valuable time, both to read and write about. Never easy, that. Robson's work makes it a pleasure. There's another difference between the Rick who read this book the first time and the one who holds it now. I've actually seen the Mappa Mundi, an incredible artifact kept in the cathedral at Hereford, where most of Phil Rickman's wonderful Merrily Watkins novels take place. The Mappa Mundi is a thirteenth century relic that interprets the world in spiritual and geographic terms. Hereford Cathedral also hosts the Chained Library, which one hopes, will become the title of a future novel by Robson. Should you get to the UK, Hereford is certainly worth going out of your way for. And seeing the actual Mappa Mundi, or even reading about it on the web pages linked here will inform your reading of the novel. You've Gotta Believe Me–it's a great book. |

|

08-08-06: Jennifer Egan Enters 'The Keep' |

|||

Ride

the Wave of Postmodern Horror

Here–Lookit this. Jennifer Egan is an author worth looking at anyway, what with her novel 'Look At Me' being a finalist for the 2001 National Book Award. Her novel 'The Invisible Circus' was adapted into a movie that was well-worth Your Valuable Time. I watched this movie twice, and never twigged to the fact that it was based on a novel, though it surely had the dense, full feel of a novel instead of the usual lightweight froth of film. Now, she's a got a new novel out, with the same title as one of the horror genre's favorites by F. Paul Wilson. As much as I like F. Paul Wilson's novel, I think we can safely set it entirely aside when talking about Egan's. Other than the title, there's no similarity or connection between the two. Well, the title and big ol' castles in, oh Transylvania, Romania, or, in Egan's novel, "Austria, Germany, or the Czech Republic." Egan's novel comes with a very nicely designed cover that manages to give a rather clever hint of what’s going on in the novel itself. John Gall should get a high five for his intelligent and attractive jacket design. Egan is likely to get a passel of award nominations, and one hopes that the various horror-oriented folks would give this book a look come award time. Perhaps 'The Keep' is not exactly a "scary book" but it certainly falls well within the purview of literary horror. The novel seems to begin with Danny and Howie scoping out a castle. As kids they first bonded creating their own sort of D&D world, but Danny got normal and Howie went weird, then turned pro. It happens that Pro weird does a lot better in the long run than pro normal, and thus Howie is thinking about buying the old heap 'o rocks to turn it into a primeval theme park, where magic might once again become real. Of course this all presumes that the narrative you are reading is "real" and not just a story being written for a prison writer's group. And once you've unlocked the door to that particular castle, then you know you're brain is really going to be worked over. In a nice, if disturbing fashion. Egan uses a lot of intelligent literary cut-n-pastes to up the ante in a novel that is part gothic horror and part naturalistic horror. She embraces the surreal and the unreal in the manner that will be quite familiar to readers of say, Peter Straub, as well as the David Foster Wallace Crowd. (And they're a boisterous crowd.) But what makes this novel really sing is the immediacy of the prose, the plunge from one reality into the next. We start reading and find ourselves elsewhere. When we find ourselves displaced while reading, we're already accustomed to the plunge. Egan takes everyone in her narrative seriously enough make us care about all the players at all the levels. It's not an easy effect to pull off, but Egan does it with the kind of effortless élan that is required. So when reality steps in once again, we're there for the ride and it is a rather impressive ride. It is the kind of book that makes you grab the person next to you, maybe just to be sure you’re there, they’re there and the book is, well, wherever books are, the readingspace that is the literary equivalent of cyberspace. Reach out from that space, and try to show someone what you see. "Hey–lookit this!" |

|

08-07-06: A 2006 Conversation With Jenn Ramage and Julia Glass |

|||

'The Whole World Over'

So I made a choice, and it was, as you'll hear, the correct one. I contacted my co-worker at KUSP, Jenn Ramage. Jenn proved to be familiar with Glass' work and went on to read the book and do the interview. Now, I can present to you audio evidence that this was the right choice, in either podcast MP3 format or RealAudio, should that choice be preferable to you. What I liked about Glass' work, and what I think her wide appeal is based on, is her ability to create personal histories based on the cascade effect of any choice; one decision of necessity begets a series of others, and every step is the beginning of a new journey. I made the choice to step back, to bow out. I'm certain that readers will agree with me that this was indeed the right choice. But I'm also aware that this choice has already favored others, and those in turn have set forth a new set of possibilities from which to choose. How to bumble into the future? So many decisions we make are disguised as necessity, cloaked in reasonable restriction. Obvious. But we do well to remember. We're always, it seems, at a crossroads. |