City of Saints and Madmen

The Untold Story

Part 1

by Jeff VanderMeer

The Agony Column for April 6, 2004

The Untold Story

Part 1

by Jeff VanderMeer

The Agony Column for April 6, 2004

Just

two weeks ago, I received the Pan MacMillan/Tor UK hardcover

edition of City of Saints & Madmen. I pick it up periodically even though I’ve

thumbed through it about a thousand times just to make sure it’s

real.

When I first conceived of a book of stories set in my imaginary city of Ambergris, I have to admit I never thought I’d be looking at an edition of it from a major publisher, using the same idiosyncratic cover design as the original U.S. version. The path from writing the stories to finding a publisher to oh-so-elusive publication has been so perilous, so littered with dead-ends and false starts, that it often seemed unlikely it would ever see print, let alone receive so much critical praise and reader appreciation. So, with City of Saints officially in British bookstores April 2, in what I consider to be the definitive edition, it feels like the right time to preserve in amber the circumstances leading up to publication. The lessons learned from this little encapsulation of some of my history as a writer and author include (1) the value of mule-like perseverance in the face of indifference, (2) the value of mule-like perseverance in the face of incompetence (including my own), and (3) the value of mule-like perseverance in the pursuit of one’s personal artistic dreams. But the main purpose of this “retrospective” isn’t to provide lessons. It’s to celebrate a book that should, by all rights, never have existed, a book about that cruelest and most beautiful of imaginary places, Ambergris. PART I: GETTING THERE In the Beginning…

I wrote the first novella, "Dradin, in Love," in 1993, during a bout of mononucleosis that kept me in a state of low-fever and fatigue for several months. I'd come back from the Clarion writers' workshop at Michigan State University less than a year before. At Clarion, I'd learned at least as much about what I didn't want to write as what I did want to write, and I’d articulated that by trying to deliberately subvert many of the accepted Clarion "rules" about story structure, characterization, and plot in a story called "Learning to Leave the Flesh."

One night, I woke from sleep with a vision of Ambergris in my head. I ran to the computer and typed out the first few pages of "Dradin, in Love." Dradin, newly returned from the jungles beyond the city, stands in the middle of a crowded street, looks up, and falls in love with a mysterious woman he sees in a window. I hardly had to revise those pages at all. The city existed complete within me. I remember the feeling of utter joy in realizing that, somehow, I had found the door to a mysterious and unique milieu. I had no way of knowing at the time that “Dradin” would lead to more Ambergris stories, but it might have occurred to me that the ease with which I wrote the beginning of the story meant related stories would also be effortless. If so, I was soon disabused of that notion. The rest of the story didn't come easily to me. I spent several months revising it. In an early draft, there was no woman at all in the end, and Dvorak the dwarf killed Dradin in a sordid back-alley scene. In yet another draft, Dvorak told Dradin the truth about the woman, took all of his money, and left him in the graveyard, with the Festival madness going on all around him. But neither of these endings satisfied me. They felt rather pat and formless. They didn't go far enough. I had been reading Steve Erickson's Arc d' X at the time--an experience that, when you have a continual low-grade fever, is quite surreal. "Dradin, in Love" was vastly different from Erickson's novel, but the way Erickson pushed the boundaries of what is possible with narrative told me that I needed to go farther with "Dradin." (I also stole from Erickson a neat trick of colliding tenses and moments in time, for a scene in which Dradin has a reverie about his childhood and his mother's thwarted ambitions.) After I'd thought about the implications of Dradin's infatuation, I finally realized I'd ended the story too early. Around the same time, I also read Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy, and constructed the fight scene between Dradin and Dvorak as a kind of minor homage. (The entire story I saw as my tribute to English author Angela Carter—not pastiche, but my approach to the same subject matter from a man’s point of view, which would necessarily comment on the objectification of women in a very different way.)

After I made these adjustments, it was time to send "Dradin" out for publication. However, I soon found that selling long novellas wouldn't be as easy as selling short stories. By 1993-94, I'd sold literally dozens of stories to a cornucopia of professional, semi-professional, and indie press publications. I expected that "Dradin, in Love" would be the piece that put me over the top and make it even easier to sell my stories in the future. Instead, it marked the beginning of a six-year stretch during which I found it hard to sell any fiction at all. Dradin, in Limbo

I remember sending "Dradin" to half a dozen other large publications, each time meeting with a polite rejection. After a few of these rejections, many of which, in that pre-Internet age, took several months, I became discouraged. I sent the novella out less regularly, became embroiled in co-editing the first Leviathan anthology, wrote most of a novel that would become Veniss Underground, and gradually realized that "Dradin" was not going to be my first big success. Then, in late 1995, I won a Florida Individual Artist Fellowship for excellence in fiction--ironically enough, for a realistic, non-fantasy story called "Black Duke Blues." The fellowship amount came to $5,000, and for the first time the idea of self-publication entered my mind. I had self-published my first collection, The Book of Frog, back in 1989, and really didn't want to repeat the experience, but I had been re-reading "Dradin" and had become convinced that it was still the strongest thing I'd yet written.

We talked about it for a week or two, thinking about all of the positives and negatives, and then I agreed to the deal. Ann commissioned Michael Shores, an artist who had worked for her magazine, to do several collage pieces, one for each section of the novella. I did the layout of the interior, with help from Ann, and we got advice on the cover design from Duane Bray, an old friend from high school who has created almost all of the Ministry of Whimsy covers and who now works for the largest design firm in the world. "Dradin, In Love" came out and began to get excellent reviews. Early on, Tangent magazine and Dave Truesdale gave much-needed support to the book. The New York Review of SF, Interzone, and several other publications wrote some very nice things indeed. The only "negative" review came from Darrell Schweitzer in Aboriginal SF, who lectured on the limited appeal of such fiction, which, he intimated, was fit only for small press distribution. Certainly, I had no evidence yet that the opposite might be true, so I couldn't argue with his conclusions. Sales were steady if not spectacular. By the end of the initial sales cycle, the book had sold about 500 of the 800 copies printed (it is now sold out, and some book dealers sell it for $125 to $150) and had been named a finalist for the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award. It was also mentioned in a few articles on the best fantasy of the year. Greek and Serbian editions eventually appeared as well. All in all, Ann and I could not have hoped for a better result. Post-Dradin: Strange Cases

Now, though, the success of "Dradin" in book form gave me a surge of confidence. Before, during, and after living through the 24-7-365 experience of promoting Stepan Chapman's The Troika in 1997 (and editing Leviathan 2 in 1998), I wrote three pieces in (for me) quick succession: "The Transformation of Martin Lake," "The Hoegbotton Guide to the Early History of Ambergris," and "The Strange Case of X." (I also wrote a very short story entitled "Exhibit H" that was a precursor to "The Early History.") The experience of writing these three novellas/long stories was both similar to and different from working on "Dradin." On all three, I had a flash of inspiration that led to a first scene that required almost no revision. But with "Transformation" and "Strange Case," the rest of the story came just as easily. The rough drafts took no time at all and nothing substantive changed in terms of plot or character between the first draft and the last. "The Early History" required many hours of research of Byzantine history and thus took longer, but it too came easier than it should have. "The Strange Case of X"[1] may have written itself so easily because I never intended for it to see print. I got the idea for the story because of an illustration Eric Schaller sent to me, of the mushroom dwellers from "Dradin" as Disneyfied characters. Without that image, scrawled on the outside of an envelope, the story would not exist--and without that image, it is possible that Eric's later comprehensive illustrations for City of Saints & Madmen would not have come to fruition.

I also continued to wrestle with the question of what served the writer best: writing as part of a well-balanced and interconnected life or writing as a hermit in an old shack by the beach, unencumbered by any human interaction. In short, I was grappling with the nature of obsession as it pertains to writing. Writing the story had had another salutary effect on me personally: it had unmoored Ambergris from my imagination. Even though it was just a mental trick, every Ambergris story I wrote thereafter seemed like something separate from my mind. Somewhere out there, Ambergris existed, and I was just channeling "reports" from the place. For some reason, this liberated me, made me relax, and once again put the fun back into creating Ambergris stories. Still, I didn't intend to send it out for publication. However, when I sent the story out to my first readers, who were also my friends, I began to get phone calls from them, asking if I was okay. Not only had they identified "X" with me, but the story had had a strong emotional impact on them--to the point of dislocating them from reality. After a couple of reactions like this, I decide the story might be more than just a personal exploration--it might be something readers in general could connect to.

I never sent it out for possible publication in a magazine--I knew that no editor would be interested in a 30,000-word story disguised as a history essay with over 100 footnotes. (Although I did send it in for a Spanish short novel competition, to no effect.) My first readers sometimes didn't know what to make of it. Granted, about half of them enjoyed it. But among the others, one frequent response was "that's not a story." Another response--the one that irritated me--went like this: "Jeff, you've done a great job of background writing here. Now you know the entire history of Ambergris and you can write actual stories about the Silence and other events, fleshing out what you've summarized here." To which I replied, no--this is the story; the summary is the story. I wasn’t at all interested in fleshing out those events. A couple of people even advised me not to try to publish "Early History" because "it isn't a story." Did I agree? Not really. I have no defense for summarily rejecting half the advice I received on "Early History," except that it didn't seem to pertain to the actual text I had written. Eventually, I sent "Early History" to Jeffrey Thomas, who regularly served in the thankless role of one of my first readers, and he asked if he could publish it through his Necropolitan Press as a chapbook in a 300-copy edition. I accepted his kind offer. It sounded like the best possibility at that time. (In fact, it was the best decision I could have made--while "Strange Case" and "Transformation" went unnoticed in their initial publication appearances, "Early History" gained kudos from the likes of Norman Spinrad in Asimov's and Brian Stableford in Vector, who named it one of his books of the year.)[2] "Strange Case of X" I placed with Stephen Jones for his anthology White of the Moon. I'm fairly certain I never sent "Strange Case" to anyone but Stephen, but "The Transformation of Martin Lake" went to F&SF, Dark Terrors, Starlight, and several others, before Wayne Edwards took it for his Palace Corbie anthology.

As with "Dradin," I was convinced I'd written something special that for reasons of length, and perhaps the editors' particular slant or prejudice, or unfortunate timing, had gone unnoticed and unappreciated. By now, however, I was used to it. It had become a fact of my writing life. I could either write something different or trust in my abilities. It was a tough decision, and one that I have had to keep making over and over again. As mentioned previously, you have to admit to your deficiencies, your weaknesses, and address them. It would be all too easy to say "These people just don't get it--this is good work" and find out later that, well, they had a point. But in re-reading the Ambergris novellas, I still thought they were good. It wasn't that I couldn't see fault lines in them--every story has a fault line or two--but that I really did believe in them. And I believed in Ambergris, too, as a compelling setting. Approaching The Book of Ambergris

I sent out queries to agents and publishers, but too many of them thought of the book as a short story collection rather than what it really was: a mosaic novel (or, as some call it, a "fix-up"; after all, major characters in one story served as minor characters in another, and so forth). A short story collection from a relatively unknown writer would not sell to a big publisher--I needed a novel. But I had a novel, I groused. It just wasn't conventional. My best chance for publication came from John Oakes at Four Walls Eight Windows, who did take a look at the book in 1999 (at that time it was just called The Book of Ambergris). He called me to tell me he loved the writing, but that the stories weren't commercial enough and he couldn't do anything with four novellas--I should send him a novel. (At this time, a relatively polished version of my SF novel Veniss Underground was being sent around by my agent, a very nice woman in England who usually marketed children's books, so I had that sent to him, but he didn't bite on that, either, despite being remarkably nice in rejection.) Soon, I'd run the gamut of the larger publishers who might be willing to take a look at a book composed of four interlocking novellas. Then I happened upon Invisible Cities Press, who liked the work and began to dance around the idea of publishing an Ambergris volume. This seemed to be more and more of a possibility, until the night I received an email from my editor contact at the press. She asked if I would consider rewriting the stories and setting them in Paris around 1900. If I could also get rid of the mushroom dwellers, that would be great. I sent an angry email in response--one of the few times I've thought later that I was justified in sending such an email--and pulled the manuscript. For a few months, Alan M. Clark of IFD Publishing toyed with doing the book, but a combination of my own paranoia (that old mental flinch acting up; a misunderstanding over whether or not I might have to change my fiction to match the proposed art for the book), bad-timing, and a reluctance on my part to have one artist create all of the illustrations, scuttled that opportunity, although it did leave the collection with a name: City of Saints & Madmen. Clearly, City of Saints & Madmen was cursed--fated to sail, rudderless and almost-publisher-less, until it struck some kind of immovable obstacle and sank… The Strange Case of "S"

Sometime thereafter, in, I think, August of 2000, I received rather incredible news. In an act of desperation, I'd photocopied "Transformation" from Palace Corbie and sent it to the World Fantasy Award judges. I didn't think for a second that they'd even read it, but, suddenly, there it was on the ballot--as a finalist for best novella! I've never been more shocked in my entire life. Well, that is until "Transformation" actually won, in a tie with a novella by Laurel Winter. I think my jaw literally dropped when I heard that news. For the first time in my career, I felt that, in some mysterious way, I had achieved a validation I had never known I needed. Now that I had it, it filled me with renewed energy and purpose. Almost as importantly, the award would create even more momentum for the book. It should have, but plans kept changing--first the novellas were to be published as separate volumes in slipcases, then as one volume. Dr. S. hired a videogame designer to do an Ambergris game as a special bonus feature. I received one email from the man and then never heard from him again. At one point, I was to do a reading from "Transformation" for a CD. None of these plans actually came to fruition, and I kept asking Dr. S. why we weren't keeping our focus on the goal of getting the book out, rather than wasting energy on all of this peripheral stuff. But worse was to come. All throughout this process of yes-this and no-that, I had been collecting advance orders for the book from friends, family, and co-workers. I then wired the money to Dr. S. It was quite a lot of money. I thought that collecting the orders would make Imaginary Worlds Press give extra attention to my book. A few months passed. The book seemed no closer to being published. Finally, Dr. S. admitted that Imaginary Worlds Press had some financial trouble, and that he was moving my book and a few others over to an outfit called Prime Books, which I had never heard of before. Dr. S. would send the advance order money to Sean Wallace, the head of Prime Books, so that Prime could fill those orders without incurring any kind of loss. In March of 2001, I began to have extended e-mail correspondence with Sean. Sometime between March and May, it became clear that Dr. S. had never told Sean about the preorders, and had never sent Sean the preorder money. E-mails to Dr. S. resulted in e-mails back full of excuses or empty promises. It appeared that Prime was going to have to eat the advance order monies if they wanted to publish the book.

Whatever the truth of Dr. S.'s situation, it was only with much effort--I dogged Dr. S. like the paper boy dogged John Cusack's character in the movie Better Off Dead--that Prime ever saw even half of the advance order money again, much later. Cutting a deal with Dr. S. on this issue--I agreed to drop my request for the rest of the money back--meant Sean would take only a small loss on the pre-orders. In the meantime, Sean offered a trade paperback deal through John Betancourt's Cosmos Books, which Sean ran for John. I accepted, and work commenced on producing that edition. Unfortunately, publishing the hardcover before the trade paperback was hampered by the situation with Dr. S. and also by a glimmer of a glint of an idea that had begun to take shape in my mind. So, despite the illogic of putting out a trade paperback before a hardcover, the first edition of City of Saints was the four-novella trade paperback from Cosmos Books. Published to considerable acclaim, it made Locus Magazine's Recommended List and received great reviews in a number of prominent publications. China Mieville, basking in the success of Perdido Street Station, provided a blurb, as did several others. Nick Gevers, Michael Levy, and Brian Stableford all gave the book great support. Finally, I could relax. Except, the Cosmos edition of City of Saints proved to be only the beginning of the City of Saints story. Months and months of preproduction hell lay ahead, created in part by my unrealistic expectations and the limitations of print-on-demand publishing.

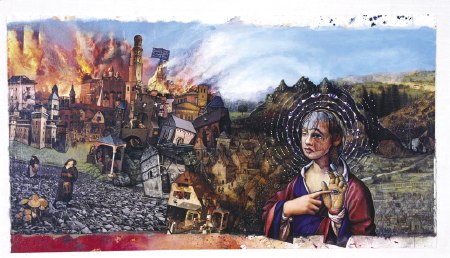

Illustration credits: Eric Schaller, mushroom dwellers; John Coulthart for the title pages; Scott Eagle Cover art (above)

|